Google Books now has the full content of LIFE Magazine available online. There are two articles on American volunteers: March 28, 1938, Americans Have Died For Democracy in Spain, pp. 56-57; October 31, 1938, American Fighters Against Fascism Come Home From Spanish Civil War, p. 17.

Google Books now has the full content of LIFE Magazine available online. There are two articles on American volunteers: March 28, 1938, Americans Have Died For Democracy in Spain, pp. 56-57; October 31, 1938, American Fighters Against Fascism Come Home From Spanish Civil War, p. 17.

The Lincoln Brigade in Life Magazine

Book Review: Ernest Hemingway’s pal

Grace Under Pressure: The Life of Evan Shipman. By Sean O’Rourke. Harwood Publishing and Unlimited Publishing, 2011.

Grace Under Pressure: The Life of Evan Shipman. By Sean O’Rourke. Harwood Publishing and Unlimited Publishing, 2011.

“I owe Spain a great deal,” Evan Shipman wrote to his good friend Ernest Hemingway on his return from Spain in June 1938. Shipman’s road to war followed a unique path that was influenced by the novelist. He traveled to Europe in February 1937 when Hemingway donated ambulances to the Republican government and asked Shipman to deliver them. Shipman turned over the ambulances to the American Medical Bureau in France and attempted to travel on to Spain. Shipman, whose passport was stamped “Not Valid For Travel to Spain,” was arrested by the French border patrol and jailed for his attempt to enter Spain with volunteers for the International Brigades. During his eight-week incarceration, Shipman formed a close bond with other volunteers.

When he was released from jail, Shipman completed his journey and enrolled in the International Brigades. After recovering from wounds sustained in action at Brunete, while serving with the Washington Battalion, Shipman remained at Murcia as hospital commissar. In January 1938, he transferred to Madrid, where he worked for the Ministry of Propaganda on Voice of Madrid. In the late spring of that year, Shipman returned to the Brigades. He moved to Barcelona, where he served briefly as the editor of Volunteer for Liberty before his repatriation. After his return to the United States, Shipman joined the Veterans of the Lincoln Brigade and maintained a cordial relationship with them throughout his life, despite being essentially apolitical.

Evan Shipman might be forgotten were it not for his friendship with Ernest Hemingway. As Sean O’Rourke notes, most of what is written about Shipman in “literary histories and books about his better known friends is often incomplete, inaccurate, or just plain wrong.” O’Rourke’s well researched biography provides an engrossing narrative history of Shipman and his milieu that draws a more accurate picture of a complex character.

Shipman aspired to be a poet and author and published numerous poems and a novel; however, his indifference to financial matters, poor health, and a difficult marriage led him to make a living as a journalist. His intimate knowledge and love of horse racing, both in Europe and the U.S., led him to be memorialized as the “dean of American turf journalists” upon his death in 1957.

O’Rourke’s considerable research is evident. Over the course of five years, he delved into the archives of ALBA, Harvard, Yale, Princeton, and the Sorbonne. In each chapter O’Rourke frames Shipman’s life through the people with whom he interacted. A website with additional photographs, corrections, and amplifications can be found at EvanShipman.com.

Chris Brooks maintains ALBA’s biographical dictionary of the U.S. volunteers in the Spanish Civil War.

Book Review: Ivor Hickman, the last to fall

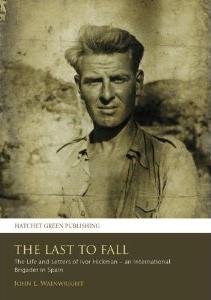

The Last to Fall, The Life and Letters of Ivor Hickman – an International Brigadier in Spain, by John L. Wainwright’s. Hatchet Green Publishing, 2012.

The Last to Fall, The Life and Letters of Ivor Hickman – an International Brigadier in Spain, by John L. Wainwright’s. Hatchet Green Publishing, 2012.

From the cover photograph, of the International Brigade volunteer’s weather-beaten face to the closing lines of The Last to Fall, The Life and Letters of Ivor Hickman – an International Brigadier in Spain, John L. Wainwright beautifully intertwines the personal correspondence of Hickman into the broader context of the British Battalion. The photograph, taken during the height of the Ebro Campaign, shows a soldier who appears to be in his thirties, with worry lines etched into his forehead and a tired squint. The image belies Ivor Hickman’s youth. Hickman, the Chief of Observers for the English Battalion, was only in his early twenties when the photograph was taken.

Wainwright’s work takes the reader through the brief life of this almost forgotten Spanish Civil War volunteer. The letters Hickman wrote to his wife both during their courtship and his time in Spain are the focal point of this work. Hickman was a young man with a great deal to live for. He was only 23-years-old and married less than a year when he died in Spain. As his letters convey, he was committed to surviving the war, exercising every opportunity to obtain training aimed at increasing his chance of survival. Despite his training and optimism, Hickman understood the dangers of war and that one cannot ensure his own safety on the battlefield.

Hickman had an impressive education. He attended Peter Symond’s preparatory academy on scholarship after his father, an officer in the Great War, committed suicide. In light of contemporary psychology and the study of combat’s aftermath, it can likely be concluded that the elder Hickman suffered from Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). An outstanding student at Symond’s, Hickman was accepted to Christ’s College, Cambridge University, graduating in 1936. While at University, he developed liberal political leanings and joined the Cambridge Communist Party. While still a student himself, Hickman met his future wife, Juliet MacArthur, a student at Newnham College, Cambridge University.

Hickman’s letters are introspective and contain less of the propaganda element many other volunteers interjected into their memoires and correspondence. Despite self-censorship, and strike-outs by the censors, Hickman provides a very human portrait of his service in Spain. Wainwright provides context, adding short biographical sketches, either in the text or in footnotes, of volunteers Hickman mentions in his letters. This element is strengthened by Wainwright’s inclusion of photographs of the volunteers when available. Additionally he includes relevant primary sources and provides transcription. Wainwright’s extensive research is evident and his narrative is engaging. This book is a must read and is a worthy addition to Spanish Civil War libraries.

Chris Brooks maintains ALBA’s biographical dictionary of the U.S. volunteers in the Spanish Civil War.

Spanish Civil War Pamphlets Accessible Online

The Internet Archive, a 501(c)(3) non-profit, has several pamphlets and magazines related to American volunteers in the Spanish Civil War in its online collection. These open source documents provide access to materials normally accessible only within an archive. All of these items were published for fundraising and propaganda purposes and provide a view of what was being consumed on the home front. The items available include:

From a Hospital in Spain, Nurses Write. Medical Bureau to Aid Spanish Democracy, [1937]. This fundraising pamphlet includes letters, or excerpts of letters, from nurses and other female personnel in the American Medical Bureau. Letter writers include Mildred Rackley, Fredericka Martin, Rose Freed, and Lini Fuhr. An interview with Dr. Edward Barsky is also included in the pamphlet. Link here.

From the Cradle of Liberty to the Tomb of Fascism. The Communist Party of Eastern Pennsylvania, undated [1938]. The pamphlet publishes a collection of letters written by volunteers from Philadelphia. Most of the letters’ authors are identified. The list includes Earl Luppo [Leppo], Morris H. Wickman, Steve Nelson, Joe Drill, Andrew Pape, Manuel Shapiro, Joe Dougher, Martin Hourihan, Harry Walach [Wallach], and Barney Spaulding. Among the letters signed with only a first name is one signed by “Bertha.” From the letter’s content it is apparent that this is from Bertha Kipness, a nurse from Philadelphia, who served with the American Medical Bureau. The majority of letters were written between May and August 1937. Several of the letter’s authors were later killed in action.

In addition to the letters, the pamphlet includes a list of men from Philadelphia who were killed in Spain including Joseph Seligman Jr., Luigi Barrelli[?], Morris H. Wickman, Chester Mujlianas, George Dyken, Dmitri Semenoff, John Johnson, Robert Greenleaf, Konstantinos Romanzes, Aino Petaya and Frank Watkins. It is also one of the only sources to mention John Parks, one of the first American volunteers to die in Spain. He was killed when two trucks carrying Lincoln Battalion soldiers to the Jarama Front took a wrong turn and passed into enemy lines. It notes “John Parks in the Hands of the Enemy since February 28, 1937.” Note the date listed is twelve days after the trucks were lost on February 16th. Link here.

Letters from Spain, by Joe Dallet American Volunteer to his Wife. New York Workers Library Publishers, 1938. A collection of Joe Dallet’s letters home to his wife, published after his death at Fuentes de Ebro. The pamphlet includes a biographical sketch of Dallet along with brief memorials by William Foster, Earl Browder, Tim Buck, Steve Nelson, and John Williamson. Link here.

Letters from Spain, by Joe Dallet American Volunteer to his Wife. New York Workers Library Publishers, 1938. A collection of Joe Dallet’s letters home to his wife, published after his death at Fuentes de Ebro. The pamphlet includes a biographical sketch of Dallet along with brief memorials by William Foster, Earl Browder, Tim Buck, Steve Nelson, and John Williamson. Link here.

Next Step to Win the War in Spain. Workers Library publishers, January 1938. Transcripts of speeches presented by Earl Browder, Head of the American Communist Party, and Bill Lawrence, former Albacete Base Commissar. Link here.

Southern Worker, Magazine of the Common People of the South, Vol. 5, No. 16. Chattanooga, Tennessee: Communist Party of the USA in the South, July 1937. This issue includes an article on volunteer Fred Williams’s family by Pat Barr titled “Mary And I Are Glad Our Son Went To Spain.” Although Williams was previously identified as an African American, this article suggests he may have been Caucasian. The article focuses on the family and their working class background. Williams did not return from Spain and it is assumed that he was killed in the closing stage of the Ebro Offensive. Link here.

Southern Worker, Magazine of the Common People of the South, Vol. 5, No. 17, Chattanooga, Tennessee: Communist Party of the USA in the South, September 1937. The magazine features Alabama volunteer Kenneth Bridenthal on its cover and reprints a letter previously published in the Birmingham Post. Link here.

Story of the Lincoln Battalion, Written in the Trenches in Spain. New York: Friends of the Abraham Lincoln Battalion, [1937]. This is the pamphlet written by volunteer John Tisa that focuses on the first actions of the Lincolns. It is the earliest published account of the Jarama period. Link here.

Chris Brooks maintains ALBA’s biographical dictionary of the U.S. volunteers in the Spanish Civil War.

Albin Ragner: An Unpublished Memoir

Albin Ragner and Dr. Arnold Donowa aboard the President Harding in December 1938. (ALBA Collection).

Editor’s note: This is the first in a series of biographies of Lincoln Brigaders by Chris Brooks.

Albin Ragner was born on March 7, 1918, in Waterbury, Connecticut to Lithuanian immigrants Charles J. Ragner, a conveyor operator for a gas company, and the former Ann C. Kieturikies, a housewife. Later, Ragner, his parents and his brothers, Alfons and Anthony, moved to Milwaukee, Wisconsin. [1] There, he completed high school and began working in railroad maintenance.[2]

When Ragner decided to volunteer for the International Brigades early in 1937, a friend helped guide him through the process. His passport was issued April 5, 1937, and listed his address as 1923 South 15th Street, Milwaukee, Wisconsin.[3] On April 19, 1937, Ragner left Milwaukee and travelled to New York where he boarded the Manhattan for his voyage to Europe. [4] Unlike many volunteers he did not receive a medical exam.[5]

When the Manhattan docked in Le Havre, Ragner took a train to Paris. On May 2, Ragner and a small group of volunteers departed Paris by train en route to the Spanish border. Over the next couple of weeks, Ragner stayed in various hides as he waited to cross the Pyrenees. At age 19, Ragner was younger than most of the American volunteers and in excellent physical condition. He easily kept up with the guide whom he described as having “legs of iron,” while at least three other volunteers in his party had to turn back. Ragner’s group arrived at the Spanish border guard station at dawn on May 19.[6]

A truck took the volunteers to the old fort in Figueras where they rested for one night. The following day they boarded a train to Valencia. After spending the night in the city’s bull ring, trucks arrived and took them to Albacete. In Albacete, he formally enrolled in the International Brigades and was sent to Tarazona, the American training base.[7]

When Ragner arrived at Tarazona, the George Washington Battalion was there training. They enrolled Ragner as a signalman and runner. He fought with the Washington Battalion through the Brunete campaign. When the Washington Battalion merged with the Lincoln Battalion, he was assigned to the 3rd Company of the Lincoln-Washington Battalion. Ragner fought at Quinto, Belchite, Fuentes de Ebro, Teruel, Seguro de los Baños and the Retreats with the Lincoln-Washington Battalion. At the close of the Retreats he transferred to the Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion’s Company 2. He had lost all of his close friends in the heavy casualties faced by the Lincoln-Washington battalion.[8]

During the Ebro Offensive, Ragner was promoted to Corporal and commanded a light machine gun team. On September 18, 1938, in the Sierra Caballs, he received orders to set up his gun on a ridge. Ragner emplaced his gun and crew during the night. The following morning they were in action against Nationalist guns on a facing height. During the fight, Ragner’s crew was killed and he sustained a wound to his right leg. A fellow volunteer risked his life to pull Ragner from his exposed position enabling him to be evacuated. Ragner remained hospitalized until eventually evacuating to France.[9]

Ragner returned to the U. S. on December 31, 1938, aboard the President Harding. He was sent to the Jewish Hospital in the Bronx for additional assessment and treatment. The leg wound, which did not fully heal until 1940, prohibited Ragner from serving in the military during the Second World War. During the early years of the war, he worked as a seaman on the Great Lakes. In November 1941, after two years on the job, he experienced a complete physical collapse. After his physician advised Ragner to avoid working in shops or plants, he began studying drafting at the Milwaukee Technical Training School.[10]

On January 3, 1942, Ragner married Claudine Halliwell. They had three children together Daniel in 1946, Allison in 1948, and Johnathan in 1954. His family enjoyed camping and purchased a lake house for vacations.[11]

In 1950, Ragner found employment as a draftsman in the Engineering department of the Oilgear Company, in Milwaukee. He remained with the company until his retirement in 1982. Ragner became a Master Mason in 1980 and was very active in Masonic activities until his death on April 3, 1996.[12]

Later in life, Ragner wrote a short memoir, which we transcribe here:

Memoir Albin Ragner a. k. a. Albin Ragausky

This is the story of my service in the Spanish Civil War during the years 1937 and 1938 as a soldier in the Abraham Lincoln Brigade of the 15th Brigade of the International Brigades.

I became very interested in Spain, especially when the country erupted into civil war. I felt that the Spanish people were fighting for their democratic republic, against General Franco’s forces who were in open revolt against a duly elected government. The people of Spain were going to suffer repression by this fascist and his armed forces, and this later became fact.

I decided to volunteer for the International Brigades, in existence in early 1937. After the battle of Guadalajara was fought and over with, I departed for Spain, leaving Milwaukee on April 19th of 1937. I was 19 years old at the time. I left for New York to contact people who would help me to cross to the Spanish conflict. I was in New York for about five days. I had just enough money to cross to France and no more. [1] I paid my fare over on the S. S. Manhattan.

I was told the contact would meet me at the dock in Le Havre, France. I arrived there about the 27th of April and was taken to Paris by train. The guide spoke French and English. I stayed in Paris until May 2, 1937. I left Paris by train for a town north of Lyons, France, and from there a bus took us to a village in the Jura Mountains 20 miles from Lake Geneva. About three days later we left by bus for the rail line, and from there were taken to Lyons. After two days in Lyons, we went on to Agde, France, on the Mediterranean coast. At that time, it was a small fishing village and market. The fishing boats came back from a day’s fishing with fish and squid. From Agde we could see the Pyrenees.

We left Agde by bus for Perpignan near the border on the French side. We stayed under cover for three days, during which time our group was broken up into groups of three men as we were too many for any one home to shelter us. In the night of the fourth day we moved to a building under construction, where a truck picked us up and took us to hilly terrain. We were concealed in rough terrain and spent the day here. When dusk came a French-Spanish guide arrived. First he fed us. Then he instructed us to be quiet, we were to cross a large farm. We were informed a road in front of the farm was patrolled by the French border patrol. After crossing the road in a rush , we were in the foothills. Our guide told us there would only be one brief stop and then on to the Spanish border guard station.

The view from the top of the mountains was spectacular. We saw the lights of one town far below. I was cold. We lost three stragglers. I was the third man in line and kept up with the guide and second man. The guide had legs of iron – the worked like pistons. I was in tiptop shape for this climb and came out fine. We arrived at sunrise at the guard station.

A truck picked us up and we went down a very winding road, arriving a Fort Figueras in Catalonia, Spain about 10:00 a. m. on May 19, 1937. We stayed here one night and a truck took us to a railroad station where we boarded a train to Valencia and stayed in a bull ring overnight. Then, on by truck to Albacete, the city where arrivals were sorted for final destinations. Being American, I was taken to Tarazona.

Tarazona

I found the Washington Battalion had been in training a couple of months. In this case I was placed in the signal squad which I didn’t enjoy. Anyway, I received intensive training in late May and early June. I very much wanted to be in a rifle company but ended up a signalman and battalion runner. Though the training was speeded up, I didn’t mind.

It was at Tarazona I met two Lithuanian Americans from Worcester, Massachusetts. These were Tony Mazurka and his buddy Jay-Jay.[2] We filled in our evening hours at the Vino Casa. Tony, so easygoing and happy was a joy to be with and so was Jay-Jay. Also with us were Tom Danek,[3] a Canadian from Windsor, Ontario who was from a miner’s family and Ben Goldring[4] from New York. Another Lithuanian was Chesna[5], a big fellow. These companions were the highlights of my stay in Tarazona, which was about 20-25 miles from Albacete. The townspeople were good to us and we were good to them.

About June 28, we packed up and loaded trucks with machine guns and ammunition for the 4th Company, the machine gun company. In the last week of June 1937 we were moved up behind the Jarama front at Madrid. We were located in a large olive grove very close to the Tahunia River[6]. Here, looking up at the hills before us we could hear and see Franco’s artillery shelling the Republican Army positions. One night it rained awfully hard as both fascist and our artillery opened up. We were ordered to stand by out in the rain and marched to the hills where the artillery was firing. The only thing that balked our march was the fact that the bridge had been submerged by the torrent of rain. We linked our arms to keep from being swept away in the river. We finally got across, formed in squads, and advanced through the mud at a slow pace. Dawn seemed to come awfully slow but it did come. The artillery duel subsided and we tried to dry out. Action here at the front died down.

Around July 2, 1937 trucks picked us up at night and took us to another sector of the Madrid front. We were dumped on a road and slowly marched at dawn. I saw one road sign showing El Escorial going to our left. We kept going ahead. The terrain here was very rough with huge boulders strewn all around where a stream coursed through a ravine. We were told to be alert to high flying reconnaissance aircraft of the enemy, to freeze and blend with the rocks and not look up, to avoid detection.

Brunete

On the 5th of July we were issued cognac rations, one cup, so we knew the hour had come. On July 6 our artillery bombarded Villanueva Canada and our air force strafed enemy positions. The Lincoln Battalion was in front of us. We were in single file on both sides of the road. Then we left the road and advanced to our left through rough ground. The Lincolns were in a ravine, slowed up by enemy fire. The Washington began a flanking movement to the right and began crossing a wheat field.

Here Leo Kaufman[7] was wounded in the lung. Another soldier and I positioned ourselves on each side of him and eased him to safety. The bullets were snapping around us. We had no cover. Two stretcher-bearers then took over. We resumed our advance until we came to a road leading to the north end of Canada. Along the side I saw one of our men dead. He had the rear part f his head blown off, a real mess.

We were ordered not to enter Villanueva Canada but skirt it and advance north of the town along the main highway. Here we saw where our air force had shot up enemy reinforcements. We advanced about ten miles and turned left on a dirt road. Here began a series of low hills and here we encountered enemy sniper fire. We sent flankers to flush them out.

We now headed west for the Guadarrama River about twelve miles distant and stopped just short of the river. Overhead an aerial dogfight ensued, about two hundred planes engaged in combat. Our field kitchen was bombed. We waited until night and were fed tinned beef.

Around July 7, 1937 we crossed the dried up Guadarrama River. It was very hot. We met enemy forces on the hills beyond the river, overrunning their slit trenches. These troops were the Spanish Foreign Legion (Portuguese). We forced them to retreat with six Russian tanks blasting away at them. I stopped beside one dead Portuguese soldier and came up with a can of anchovies. They tasted great.

In this engagement my buddy Tom Danek was wounded in the thigh. He was laying telephone wire. Tom was an exceptional soldier.

I also met Robert Browning[8], another Canadian. Robert Browning was considerably older than any of us, and what floored me was he had been in France in World War I. He was with the Canadian forces at that time and fought at the battle of Vimy Ridge. He told me he didn’t mind artillery fire but dreaded bombers dropping bombs. I told him he did not belong here with us. He was too old. I convinced him to get out of the battalion and go home. He did so.

To get back to the action here, we advanced over the hills just west of the river and ran into Moorish troops who gave us serious opposition. At the top of these hills we could see Mosquito Ridge of the Guadarrama Mountains. As we approached these low mountains, Moorish sniper fire increased. One of our company commanders, Hans Amlie,[9] borrowed a rifle for a moment, steadied it on a fellow’s shoulder and brought down a Moorish sniper out of a tree.

When we reached Mosquito Ridge we were stopped just short of midway up. Here our casualties were heavy. We suffered a lot of men with head wounds. We had to dig in with our helmets. You would be surprised how fast you can dig with a helmet when forces to do so. We were in an awful situation here: Moors about 60 to 70 yards ahead. Getting our wounded out was extremely dangerous. We were thus held up for about nine days. We were relieved by some Marineros (Marines)[10] from Catalonia. This was done at night. One thing I want to mention is that all the men in the battalion carried bayonets on their rifles, and we were trained in their use. I appreciated that.

To the south of us a threat arose at Villanueva del Pardillo. We ate quickly and set off along the Guadarrama River banks in an all night march. We reached some hills and along the crest were trenches which we occupied. We relieved a company of Spanish troops at this area. We had no breakfast that morning, but at noon some food arrived by mules. Sidney Graham[11] of New York and I were given field glasses (one pair) and told to watch. I watched for about fifteen minutes and handed them to Sidney. A minute later he fell to the bottom of the trench, dead. He had a bullet hole in his forehead. I realized it could have been me. The enemy troops opposite us were Moors, and they were excellent shots.

For two days nothing of action by the enemy developed so we were ordered back to the are we had left. Other Spanish troops took over at night. It was morning and dawn was breaking before we neared our destination, when we heard the heavy drone of bombers. We knew we didn’t have such heavy planes. They saw us. I looked up once and saw about twenty bombers flying in groups of threes. The first ones released their bombs. I saw those bombs slanting down on us, then turned face down. The bombs exploded around us. I was flung up from the concussion. It threw me around like a rag doll. The planes that followed released their bombs. For ten minutes or so the world seemed upside down. The concussion is unspeakably devastating on men.

The bombers made only one mistake – - they crossed at a 90 degree angle. Otherwise our casualties would have been horrendous. We did suffer half a dozen dead. One was a nice guy called McQuarry[12]. He was badly mangled. We buried him in the sand of the river bed. The enemy artillery fired at the dust cloud rising above our position. They sounded puny compared to the bombs of the planes. This was the first aerial bombardment of many I was to be a target of. They were awesome, especially the shrill whistle of the bombs coming down.

When we arrived at our destination on the river bank at about 8:00am, we were told food was coming and it did. We were enjoying it when who comes streaming by but the marineros of Catalonia in retreat. We grabbed our rifles and took positions along the bank. The enemy bullets and shells hit our area very soon after.

I took up a position in a wooded area which had a good view of a good stretch of the river and began to snipe. One officer of the enemy caught my eye. His uniform had a red stripe on the pants, which were blue. I drew aim and hit him with the first shot. He fell over a rise of the river bank. I fired five more shots and his body jerked. It was then that troops attempted to remove his body. Whoever that officer was he was of high rank.

We battled all day at this spot. At night we formed two platoons of seven men each. I led one group and Chesna led the other. Chesna and his men ran into a large group of enemy soldiers and he was killed. He was a great fighter. Tony Mazurka was wounded in the side in this action.

The front stabilized and we were replaced by Spanish troops. In all these actions we lost over three hundred men killed and wounded. The Lincolns lost even more. We then marched back about eight miles to a reserve position among olive trees.

The next day we heard the drone of bomber engines: twelve Junkers bombers flying above the main road. Across the road from us was a Czechoslovakian antiaircraft unit which opened up on the planes. They hit the lead plane which exploded into a white cloud or puff. All we saw was a fragment of a parachute with parts of a body still attached. What a weird thing.

We were taken by bus to Tarazona, the base for the Washingtons. Here we were made into one battalion and called the Lincoln-Washington Battalion. We retrained for our battles to come. I was assigned to the third company. The company commander was Arnold Staub[13], a short, lightweight man who had been a jockey back in the States. He sure was a tough commander. I knew he would do well. One thing he sure liked was Malaga wines. So did I, only that is a dark, sweet wine and gives one a bad hangover.

Quinto

Our retraining ended in about the middle of August, 1937. Trucks were boarded and off we went at night. We went a long way, arriving on the Aragon front, and disembarked into a wooded area. Around August 27 we positioned very near to three batteries of our antitank guns, which began firing at enemy fortified positions over a main road.

We saw enemy troops take up positions west of a church cemetery. We attacked them and drove them into the church. Our anti-tank guns were then turned on the church which the enemy fired from. Six of us ran to a position north of the church. We climbed through a window into the church vestry. The door leading to the church was open. I had six grenades with me like the others of our group. I then made the mistake of stepping into the doorway and yelling, “Manos arriba.” They were lined up against the opposite church wall. They turned their rifles toward me and I ducked back fast as the bullets hit the wall. I was lucky then.

We crawled out and told our commander the enemy wasn’t going to surrender. He telephoned the antitank group for more gunfire. By this time the west side was only rubble. Our antitank guns fired about a half hour more before they surrendered to us.

We had to see if there were any stragglers still left. Not a pleasant job. We had to go up in the tower with our hand grenades at the ready. Tom Danek and I saw that a position in the cemetery would give us a good field of fire into the fortified trenches covering the main road. We could observe them scuttling along their trenches. We kept this up well past noon and then they waved a white flag and surrendered.

We heard gunfire in the valley near a cement factory by the main road. The commander of the 3rd Company said it was the Dimitrov battalion cleaning up on Moorish troops. We took about 125 troops off the fortified position.

That night Tom Danek, I and our company slept along the side of the church. The next morning our trucks picked us up and moved us in a northwesterly direction. It had taken us three days to take Quinto. Our trucks passed by with piled up bodies of dead Moorish soldiers. They had been doused with gasoline. The stench was horrible. We arrived north of Belchite about September 1, 1937. Our trucks dumped us and departed. They never stayed long because of enemy aircraft.

Belchite

We were about five miles north of Belchite. We approached in combat formation to the outskirts and in sight of the Roman Catholic Church, which was the dominant building. We soon were receiving gunfire from the church tower. Our company, in spread formation, advanced up terraces led by Arnold Staub, commander of 3rd Company. Advance was slowed by heavy gunfire from the church tower. I had a full supply of grenades in a shoulder bag. I went over the rubble tossing grenades. Others did the same and so did another group from the west side of the church. This group lost Dan Hutner,[14] killed by sniper fire.

We were close to the church on the north side. It had a square tower. We made our breach through this wall amidst rubble which our antitank and artillery caused. We scooted over the rubble throwing hand grenades to blast enemy troops before us. This type of fighting is extremely dangerous.

We forced them into houses on a street leading to the church. We stayed fifty yards from these houses protected by a wide and deep gully. We had reached this point exhausted. I fell asleep and just before dawn a fellow shook me awake and said ten minutes and over we go. We made the charge and broke into two houses. Grenading our way through, everything seemed to explode into the explosions. When grenading a house he had to keep from getting into the house at the wrong time, or we too would die from the concussion.

The first house I entered I made a mistake. I took a quick peek out the front door. Across the street on a roof an enemy soldier tossed a grenade which landed at my feet. I was paralyzed with fear, then I took a running start and dove out the rear door. That was one of my lucky days. The grenade wan an Italian concussion type. It is very unusual for a grenade to be a dud. I sure think someone was watching over me.

Anyway, we forced the enemy out house after house, compressing the enemy to the central plaza where the main buildings were. We fought them here for about three days. One night the enemy used women and children as a shield, this in the very early morning before dawn. We couldn’t fire at the troops because of the danger of killing civilians. We were helpless.

Dan Hutner, a front line buddy of mine, lost his life in a courtyard between the church and a factory. He was from New York. He was an inspiring man and a terrific fighter. I could never forget him even after all these years. When I first came home from Spain, I was in the Jewish Hospital in the Bronx, New York. His brother, Leo Hutner, came to see me. I told him what happened. I had buried him near the church at Belchite.

Our losses were heavy in the seven days of fighting. Hans Amlie, our battalion commander, was relieved of his command because he couldn’t bear such huge losses of life. He was replaced by Steve Nelson. We were relieved by Spanish troops. After September 7, we had a brief respite through September.

Fuentes de Ebro

About the eighth or ninth of October we were transported to Pina, which had been taken by the Lister Division. From here we marched northwest to just three miles from Fuentes de Ebro. Fuentes de Ebro was a town twelve miles from Zaragoza, our ultimate objective.

We dug in to positions near Fuentes de Ebro. Enemy trenches were 300 yards off. We could see the church tower in Fuentes de Ebro. To the right of where I was, the ground dropped off thirty feet down into a flat area. Our trench was dug to cover a grape vineyard and a railroad. On the opposite side, enemy Moorish troops occupied a low building. We could hear them sing in the Moorish tongue. On two nights, we got up to the railroad bank and flung hand grenades at their building. That quieted them down.

Around the fourteenth of October we were told we would attack the enemy position and go for Fuentes de Ebro. On the fifteenth of October we were ready to attack at 6:00am.[15] We were to have the support of Russian tanks. It wasn’t until 10:00am they showed up. Much too late. They maneuvered for position and went right over our trenches. We could not keep up with them. That goofed everything up. The tanks drew antitank guan and artillery fire. We followed after and ran up against intensive machine gun and rifle fire. We were stopped. I took cover behind one of our disabled tanks. The turret was blown off and also the driver’s head. The crew was dead. We lost twenty-three tanks out of fifty. By not being able to take Fuentes de Ebro we lost our chance to take our main objective, Zaragoza.

We lost another Lithuanian American Jay-Jay from Worcester, Massachusetts. I wish I knew his name. We gained no ground by attacking too late in the morning. The enemy was reinforced heavily.

After the actions subsided, I was given a 48 hour leave to Barcelona. In all my eighteen months of action in Spain I was given a total of 96 hours leave. I bought a jacket which looked like Eisenhower’s jacket in World War II. I have a picture of myself in the jacket. Our battalion had moved out to a reserve position when I returned. The trip from Fuentes de Ebro to Barcelona took five hours.

Teruel

We stayed in Tarazona until about the middle of December, 1937. About the eighteenth of December we were transported north of Teruel to a place called Cuevas Labradas. At this time I was in the 3rd Company of the Lincoln Battalion. We were put into an unfinished railroad tunnel to hide us from enemy aircraft. The temperature was intensely cold – - about 5 or 10 degrees below zero, and the wind blew through the tunnel. At night we gathered wood to burn for warmth. It was almost impossible to keep warm.

We were soon after taken and guided to old dugouts north of Teruel. We pushed back enemy lines about a mile. The fascist troops launched an attack on our Spanish 24th [59th] Battalion, making their position hard to hold. When we launched an attack into the flank of these troops, we sure halted their attack. They must have been a regiment. We scored on them heavily and they retreated, leaving a lot of dead. I didn’t know General Lister[16] was watching our counterattack and he commended our action as saving the 24th [59th] Battalion. That was the highest praise one could get in Spain. He was the highest division commander in Spain and his division was the best known.

After this action, we were moved into Teruel about December 21or 22. What a grim looking place. They claimed there were still some enemy hiding in the town. We took up positions to the left of the Lister Division and the 43rd Division, a tough outfit.

We were behind a cement wall in an old factory. The enemy positions were only fifty yards away from us. It was awfully dangerous to even look at their positions. Charles Lisber[17] from New York City was killed here. He tried to move forward and was spotted and killed, his liver shot out. Captain Phil Detro[18] from Texas, a former U. S. Marine, was mortally wounded trying to snipe from the second floor of a building. About the end of December, we were in reserve position.

Segura de los Baños

Sometime in February of 1938 the Lincolns were transported to the Huesca front in a sector called Segura de los Baños. Here there were fortified trench hill positions which overlooked a road and a small town. These trenches were occupied by Franco forces. They could shell the road and town. The enemy forces were under the command of an Italian captain. His troops numbered about 150 men, Spanish soldiers.

We were position for the assault before dawn. The Mackenzie-Papineaus were with us in this attack. One of our men had been on leave before reaching the area. He wore a red beret. At dawn we were ready to attack and advanced on them. The fellow with the red beret confused the enemy. They thought we were the Requetés, their troops. We fired on them and they dove into their trenches. We crept up on their parapets, flinging hand grenades. After that we jumped into their trenches killing a number of them. They soon surrendered.

Tom Danek from Windsor, Ontario, was wounded on top of the parapet, his wrist shattered. That ended Spain for him. Also, Tony Mazurka was wounded a second time. I talked to him before they carried him down a path. The enemy artillery got our range and shelled our positions. One shell landed where Tony Mazurka was being evacuated and killed him. This was a devastating blow to me. I lost a very dear friend. Time and again I remember him, a Lithuanian American who fought bravely.

Retreats

About the fourth or fifth of March, 1938; we were again sent to Belchite, occupying the factory west of the church where Dan Hutner was killed in Belchite’s capture. The following day early in the morning we received orders to move out and head south on a road west of town.

We marched southwest and noticed a large concentration of soldiers and artillery. The guns opened up on us. Our Finnish machine gunners of the 4th Company set up their machine gun. They were killed shortly after. They sacrificed their lives for us.

Our battalion headquarters was dive bombed by Stukas, and large numbers of enemy aircraft attacked us. I escaped by heading into an olive grove, made a large semicircle, and again was on the road south. A number of us took this route. We tried to contact the Mackenzie-Papineaus but fascist tanks on a bluff fired on us forcing us to leave the road. Our rifles were ineffective on the tanks. These were German tanks.

The following action took place west of where the tanks fired on us. Twenty-three enemy planes strafed us. This was the start of the retreat at Belchite on the Aragon. I am convinced there had been treachery in the higher command. It looked like a well laid plan to annihilate the Internationals. The retreat bled us white; we lost so many men in those hills. We fought where we could, but without flankers we were lost. The enemy was overpowering in their drive, with tanks, planes, artillery and troops.

A number of times we were strafed. We retreated. I never once lost my rifle or ammunition, to me it meant life. Without a gun or ammo you are nothing, only to be buried. Several times we grouped and fought, but the enemy kept outflanking us. The meant fight and retreat, all the way back to the coast. I turned north from Tortosa, a coastal city. We sure were demoralized.

At this time I’d like to mention an incident involving Bob Merriman[19] our brigade commissar [Chief of Staff]. We were about eight or nine miles east of Gandesa during the retreat. We were on a high hill, good for defense. We had about 100 to 120 men here. We heard what sounded like tanks behind the hill to our front. I said to him, “It sounds like enemy tanks ahead.” He said, “It can’t be, they must be ours.” He didn’t heed what I said and Merriman and two others went to the hill and over. He was captured there. Later the fascists executed him.

At this time Leo Kaufman from New York City returned from the hospital. He had been wounded on the Brunete front battle at Villanueva Canada. We saw some enemy troops to our right. They were trying to outflank us. Leo went to check it out and we heard shooting. Leo never came back.

Shortly after, Italian troops attacked with whippet tanks. We fired through their gun slots but were not able to stop their attack. We held them back for an hour and then were forced back. I was almost hit here. I was lucky. The bullet passed right between my legs. By the second week of April, 1938, the retreat had reached the Ebro River. Stragglers were rounded up from all over and grouped into combat units. We were sure a miserable lot by then.

I would like to mention one of our men of the Lincoln Battalion, Joe Sych,[20] a Ukrainian Canadian. He was killed by a bomber in the vicinity of Mora de Ebro on the east side of the river. He was a very likeable fellow. We had a group of Ukrainians from Canada. Their voices were heard in song either at night or on the march.

Ebro Offensive

At this time I had requested a transfer to the Mackenzie-Papineaus and got it. There were not many of our men from Brunete left alive. On July 25, 1938 we re-crossed the Ebro River in row boats. I was in the Mac-Pap Battalion in the 2nd Company. Our company commander was Henry Mack[21], a very capable man. I had complete confidence in him.

We were just north of Mora de Ebro when we crossed the river. The firs town we attacked was Ascó. An observation plane flew overhead, and we fired on it. We cut west of Ascó and the river parallel to the Corbera-Gandesa road. Gandesa was our objective. Troops of our brigade were to the south of us. We advanced over desolate dry country.

We marched about eight or nine miles, moved south and ran into some Dombrowski troops who were pillaging an enemy supply depot. We crossed behind them to the south. We went up a series of hills toward a peak, the highest point, and made contact there with Moorish troops who fired on us. We lost Whitey Wahl[22] here. We were bombed on these slopes by Junkers bombers. I found that the high peak was called 481. The English battalion to our left tried to take peak 481. We gave them cover fire, but the slope was at too sharp an angle to reach the top of 481. The enemy lobbed hand grenades among our English battalion. It came to nothing accomplished. We had several night flare-ups.

Our contact was poor with the Dombrowskis. I was sent over to make contact and I almost ran into enemy troops moving back to different positions. Their clothes looked different and I was suspicious. That was a close call. I did contact the Dombrowskis and told them we were on their left flank.

We stayed on these slopes near the high peak until about August 4, 1938. We were then transferred south of hill 481 on another road to the Sierra de Pándols, 666 meters (2138 feet) high. We were to relieve the Lister Division who were up there twenty days and bombed every day. We moved up at night. There was only one narrow path up to the top. I wondered how they got the wounded out and food up those terrible positions. The place was sheer rock. This place was a nightmare. It was cold at night up there. The Lister troops come off first and then we went up. They were glad we were relieving them.

One thing I would like to mention is that the view from the top of the Sierra de Pándols was very beautiful looking eastward toward the Ebro river. A road could be seen winding to the river.

On top of the Sierra de Pándols we faced the Spanish Foreign Legion. Their positions were about 150 yards off. You had to cross a deep valley and then climb up to their position. One thing, we could not dig trenches here. We piled rock and used that to fire form. We were bombed two or three times a day. The fragments of bombs exploding on rock is awesome. You were extremely lucky not to be hit by shrapnel and stone.

I would like to mention something I had noticed for a long time. General Juan Yague, who commanded the Nationalist Army of Africa, always attacked us with Moorish and Foreign Legion troops lined side by side. This was always the case. Our 24th [59th] Battalion was bombed heavily on the Pándols. I remember one incident. One of the men in the Mac-Paps kicked a dud 105 shell to roll it away. It exploded and we didn’t need to bury him.

We found dead, unburied bodies all over. Rocks were piled on them. You could not dig graves. Tiny Anderson[23] was killed here. He was a machine gunner. A good one, too. When dawn broke over the Pándols, enemy bombers unloaded their lethal loads. These positions were pure hell. The enemy used Italian mountain howitzers to blast our positions. We found that our opposing troops were the Spanish Foreign Legion, good fighters. We captured one at night in no man’s land as he was relieving himself.

Henry Mack promoted me to corporal of a light machine gun. Prior to this I was leading night patrols into no man’s land. We held these positions for nineteen days. We sure were glad when the 43rd Division men relieved us. Those were very nasty positions to occupy. We were given a rest near Corbera.

Finally, we were rushed up the Gandesa road, where the front had erupted into action. We went into action to the right of the Gandesa road at a place called Sierra Caballs.

Henry Mack wanted my light machine gun on a high ridge not far from the road. The ridge was long, running north. We waited and ate lightly. As soon as the sun went down and dusk came, my gun crew and I moved down and then up this ridge. The action came fast. The enemy machine gun opened up on us when we reached our position. We fired at gun flashes. My crew was killed and I had to fire my gun. A burst of machine gun fire from them hit in front of my face and I rolled to the left. The next burst his near my right side. As I jumped to my left their machine gun bullets hit my leg, bowling me over.

Our troops to the north of my position were called back to their former attack station. I was out on this shoulder of the ridge alone. The moon was bright. The enemy were gradually working their way down.

Henry Mack told Patrick O’Hara,[24] of Calgary, Alberta, what had happened to my gun crew. I couldn’t get up. Patrick O’Hara called quietly and saw what a bad situation I was in. He took my wrist and dragged me off the ridge to a safer spot. He got hold of stretcher bearers to carry me to an ambulance. I was wounded on September 19, 1938 in the Sierra Caballs. If it hadn’t been for Patrick O’Hara I wouldn’t be alive today.

I was taken across the Ebro, where my old comrade Ben Goldring on New York saw my leg and sent me to the base hospital at Tarazona. I was operated on there and sent to the hospital in Barcelona. Two weeks there and I was sent to Santa Coloma de Franes, France[25] by hospital train. I was in the hospital in Paris for about ten days. From there I was sent to New York, arriving on New Year’s Eve, 1939. I spent ten days in the Jewish Hospital in the Bronx.

Reflecting on the conditions I saw in Spain, the people were willing to fight Franco. However, the various parties, including the socialists, communists, anarchists and the labor unions, did not do the Republic any good with their attitudes and bickering. Each was trying to be the lead group. There was too much politics. The Spanish troops fought bravely. The Lister Division, the Campesinos, the 43rd Division, and the Catalan troops were exceptional. I felt the embargo hurt us. Also, Germany under Hitler and Mussolini’s troops, planes, tanks and artillery did swing it for Franco. The Portuguese government aided Franco. The Spanish Foreign Legion with thousands of Moorish troops helped very much to defeat the cause.

One of the great moments of my time in Spain came as I was leaving on the hospital train. Looking out of the train window I saw a peasant and his wife holding a baby. The husband was holding a Spanish Republican flag, and they waved. That to me was an emotional moment. I felt everything I had been through was worth my suffering.

I heard through The Volunteer of Mirko Markovich’s death[26]. I feel very sad to hear this. He was my original battalion commander. He was the finest soldier I know, always caring for all of us men. He was loved by his men.

Chris Brooks, a long-time member of the ALBA Board, maintains ALBA’s biographical dictionary of the U.S. volunteers in the Spanish Civil War.

[1] http://www.ancestry.com/1940-census/usa/Wisconsin/Albin-Ragner_2p4cfd.

[3] Subversive Activities Control Board (SACB).

[8] Letter from Ragner to Brooks, March 20, 1995.

[10] Goldring draft of his article on Ragner, provided by Ragner and ARP Survey response.

[12] IBID and Card from Claudine Ragner to Brooks, postdated 2 January 1997.

End Notes

[1] Ragner most likely travelled on a group ticket purchased through the Soviet travel agency. The funds he mentions were likely a small amount of spending money issued to each volunteer to show they were not indigent so they would be allowed to enter France.

[2] Anthony Mazurka was born on January 16, 1915, in Wheelwright, Massachusetts. He was a single steelworker living in Worchester, Massachusetts when he volunteered to serve in Spain. He boarded the President Roosevelt on March 17, 1937 six days after receiving his passport. Once in Spain, he was assigned to the XV Brigade, George Washington Battalion. Mazurka likely remained behind when the Washington Battalion moved to the front as he records indicate he was serving with the Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion in August. Records indicate that at some point he served as a section leader in the British Battalion. He was wounded in action during the fall of 1937. Mazurka was killed in action on February 16, 1938, in the Seguro de los Baños. Julian James Baublis (aka Julie Babbit, “Jay-Jay”) was born on February 7, 1901, in Worchester, Massachusetts. Prior to Spain, he served in the U. S. Army for one year. He was single, a machine operator and a member of the CP. He was issued passport # 414 Boston series on March 14, 1937, and sailed for Europe three days later aboard the President Roosevelt. Baublis likely remained behind when the Washington Battalion moved to the front as he records indicate he was serving with the Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion in August. He was killed in action on October 13, 1937, at Fuentes de Ebro.

[3] Tom Danek, an ethnic Canadian was born November 12, 1917. He lived in Winnipeg, Windsor and worked as an electrician

[4] Benjamin Goldring (aka Joseph Jackton) was born on May 13, 1912, in New York, New York. He attended Seth Low, followed by Columbia and Columbia Law in 1934. Goldring was politically active and joined the Communist Party in October 1936. He was an unmarried attorney residing in Brooklyn, New York when he decided to volunteer to serve in Spain. After obtaining his passport in April 1937, he sailed for Europe in early May aboard the American Importer. Goldring arrived in Spain in late May and joined the XV Brigade’s George Washington Battalion. During the Brunete campaign he was wounded twice in action. After his recovery, he joined the Lincoln-Washington Battalion’s, Co. 3, and fought at Quinto where he was wounded again. Goldring returned to U. S. aboard the Ausonia on December 20, 1938. Goldring wrote an article for The Volunteer about Ragner, “Albin C. Ragner: Mostest First-Line Infantryman.” Goldring died on April 17, 2000.

[5]William Chestna (aka Philip B. Chestna) was born August 11, 1906. He was issued passport# 404684 on May 4, 1937, listing a Long Island, NY address. He sailed May 7, 1937, aboard the American Farmer. Chestna was killed in action at Brunete on July 25, 1937.

[6] I believe Ragner is referring to the Tajuña River a tributary of the Jarama River.

[7] Alfred Leo Kaufman, (aka Al Friedman, Oscar Everett) was 31years-old and living in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania when he volunteered to serve in Spain. A seaman and member of the Communist Party from 1932, he received passport #398407 on April 26, 1937. On May 29, 1937, Kaufman boarded the Britannic in New York City en route to Europe. After crossing into Spain, he joined the XV Brigade’s George Washington Battalion. He was wounded in action during the Brunete campaign. After his recovery, Kaufman attended officer training school and graduated in January 1938, with the rank of Teniente (Lieutenant). He rejoined the Brigade as part of the Lincoln-Washington Battalion. He was killed in action on April 3, 1938, near Gandesa during the Retreats.

[8] Robert Browning is most likely the Canadian Robert Brownlee. He was born in Smith Falls, Ontario, Canadian, c. 1888. He resided in Vancouver, British Columbia when he volunteered. He worked as a surveyor. He was hospitalized in Spain and later returned to Canada.

[9] Hansford “Hans” Amlie was born on September 5, 1900, in Coopesrtown, North Dakota. He was a veteran of the First World War. Amlie left the U. S. Army in 1919, and joined the Marine Corps until 1921. After completing his military service, Amlie became a mining engineer. He was an active member of the Socialist Party which recruited him to command the Debs column based on his prior his military experience. He received passport #24457 San Francisco series on February 2, 1937. He was living in San Francisco, California. After arriving in Spain he found that the Socialist Party had failed to establish a structure to get the volunteers into Spain. Amlie elected to continue on to Spain and joined the International Brigades. He arrived in March 1937, and joined the XV Brigade’s George Washington Battalion. Amlie was selected to Command Company 1. During the Brunete Campaign he was promoted to Battalion Adjutant after Captain Trail, an English volunteer who was mortally wounded. After recovering from his wounds and attending Officer Training School, Amlie took command of the Lincoln-Washington Battalion. He commanded the battalion during the battles of Quinto and Belchite. He was wounded a second time during Belchite and was repatriated. While in Spain, he married journalist Millie Bennett. He arrived in the U. S. aboard the President Harding on January 1, 1938. After the war he found employment running a farm in Arizona. He was killed in a farming accident in December 1949.

[10] Marineros were armed sailors.

[11] Meredith Sydnor “Syd” Graham was a 25-year old Communist Party member and budding artist when he volunteered to serve in Spain. On March 2, 1937, he received passport# 370943 which listed his address as 32 Cornelia Street, New York, New York. He sailed for Europe on March 10, 1937, aboard the Washington. In Spain, he served with the XV Brigade Estado Mayor. He was killed in action on July 18, 1937. Three of Graham’s sketch books from Spain are included in the ALBA collection.

[12]Edgar Roy McQuarrie was born June 2, 1915, in Detroit, Michigan. In 1937, McQuarrie was a Wayne State University student, active in the American Student Union, and a member of the Communist Party. On January 5, 1937, he boarded the Berengaria en route to Europe. When he arrived in Spain on February 17, 1937, McQuarrie was sent to officer training school. After completing the course he was assigned to the XV Brigade. He was an officer in the Lincoln-Washington Battalion’s Machine gun Company when he was killed on July 18, 1937.

[13] Arnold Staub was a Canadian veteran of Swiss heritage born c. 1907. He was living in Estevan, Saskatchewan when he volunteered for Spain. As Ragner noted, Staub was a jockey by profession. He was wounded in action in Spain.

[14] Daniel Hutner was a 29-year old, New York University graduate and CP member who fought and died in Spain. He received passport# 387751 on April 9, 1937, and sailed for Europe aboard the Queen Mary on April 21, 1937. In Spain, Hutner served with the XV Brigade’s George Washington Battalion. He was wounded in action during the Brunete campaign. After his recovery, he joined Lincoln-Washington Battalion and served in the Aragon Campaign. He was killed while leading a reconnaissance patrol in Belchite on September 6, 1937.

[15] Ragner’s dates on this action are off. The XV BDE’s attack at Fuentes de Ebro took place on October 13, 1937.

[16] Enrique Líster Forján was a prominent general in the Republican Popular Army during the Spanish Civil War. Lister was born April 21, 1907, in Galicia and spent part of his adolescence in Cuba. During the late 1920s, he was imprisoned for union activities. He was imprisoned when the Second Republic came to power. He joined the Communist Party in 1930 and was sent to the Soviet Union to study from 1932-35. Lister returned to Spain in 1935. When the civil war broke out, he was instrumental in raising the Quinto (Fifth) Regimento. Lister rapidly rose in rank and prestige rapidly moving from Militia commander to Brigade Commander and later to Division command. During the Ebro Offensive he commanded the Fifth Army Corps. After the war he travelled to the Soviet Union where he attended the Frunze Military Academy and became a member of the Spanish Community Party’s Central Committee. He broke from the party and was expelled in 1959. He returned to Spain after Franco’s death. Lister died on December 8, 1994.

[17] Charles Lisberg, an African American, was born February 10, 1911 in Abita Springs, Louisiana. He later moved to Los Angeles, California. In 1931, he joined both the Young Communist League and the Communist Party. Lisberg was single and working as a carpenter and laborer when he volunteered to serve in Spain. He received passport# 28772 on May 28, 1937. He travelled to New York where he boarded the Georgic on June 12, 1937. After crossing into Spain, Lisberg joined the XV Brigade’s newly formed Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion and began training in Tarazona. Lisberg was sent from the training base to the Lincoln-Washington Battalion where he served as a replacement with Company 1. He was killed in action at Teruel on January 25, 1938.

[18] Philip Lucas Detro was born in Conroe, Texas. He volunteered for service in Spain in early 1937. Detro travelled to Europe aboard the Ile de France on March 12, 1937. In Spain, he joined the XV Brigade’s George Washington Battalion as the adjutant to the commander of Company 1. During the Brunete campaign he took command of the company after the commander was wounded. Detro was subsequently wounded. After recovering he returned to the Brigade serving as a staff officer. Detro took command of the Lincoln-Washington Battalion during the battle for Belchite after Amlie was wounded. He led the battalion through Fuentes de Ebro and Teruel. He was wounded by a sniper at Teruel and died in Hospital. During his service in Spain, Detro was regarded as a maverick.

[19] Robert Hale Merriman was born November 25, 1908, in Santa Cruz, California. He graduated from the University of Nevada in 1932 and continued graduate studies at the University of California. While attending the University of Nevada, he was enrolled in the Reserve Officer Training Corps (ROTC). He was studying in the Soviet Union when the Spanish Civil War broke out. He arrived in Spain on January 18, 1937. Merriman was appointed Adjutant commander of the Lincoln Battalion and took command of the battalion shortly after it arrived at the front. Merriman was wounded in action during the disastrous assault against Pingaron Hill on February 27, 1937. His wife Marion joined him in the hospital. After his recovery he attended officer training school and later commanded the Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion while it was undergoing initial training at Tarazona. He rejoined the Brigade as the Chief of Staff shortly before the Aragon Campaign. He was promoted from Captain to Major and served through Belchite, Fuentes de Ebro, Teruel and the first stage of the Retreats. Merriman disappeared during the second stage of the Retreats, near Gandesa in April 1938. Various accounts of his disappearance have been published. The most popular is that Merriman followed Brigade intelligence officer John Gerlach into an Italian encampment. Gerlach was leading the remnants of the Lincoln-Washington Battalion in a night march as they attempted to break through Nationalist forces to regain Republican lines. Merriman is believed to have been captured in the camp and subsequently executed. Ragner’s account differs significantly and is closer to that of Fausto Villar Esteban, a Spanish officer serving with the XV Brigade who wrote a memoir of his experience with the brigade. (cited in Cecil Eby’s Comrades and Commissars, pp.331-33)

[20] Joe Sych – I have been unable to confirm Ragner’s assertion that he was a Ukrainian Canadian in the Lincoln-Washington BN.

[21] Henry Mack (aka Henry Maki, Oni August Arvitt) was born in Finland on November 22, 1909. He was a 28-year -old auto worker living in Bessemer, Pennsylvania or Ohio when he volunteered to serve in Spain. On March 10, 1937, Mack boarded the Washington en route to Spain via France. In Spain, he initially served as a Section Leader in the Machine gun Company of the Edgar André battalion of the XIth International Brigade. He fought at Guadalajara and Brujela where he was wounded in action. After recovery, Mack attended officer training school. He remained at the school for three additional months after graduating as a machinegun instructor. During the Retreats, he transferred to the XV Brigade’s Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion. Mack was assigned as a company commander and briefly commanded the battalion. During the reorganization of the battalion, he took command of Company 2. He was wounded in action during the Ebro Offensive on September 21, 1938. Mack returned to the U. S. aboard the Washington on August 8, 1938. He died on February 26, 1976.

[22] Whitey Wahl – I have been unable to confirm this volunteer’s name.

[23] Ivor “Tiny” Anderson was a Canadian of Danish descent. When he volunteered, he was living in Vancouver and working as miner. He was one of the volunteers who survived the sinking of the City of Barcelona in May 1937. Anderson served in the Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion and was killed in action in the Sierra de Pándols in August 1938.

[24] Patrick O’Hara –I have been unable to confirm this volunteer’s name.

[25] I believe that Ragner may be referring to Santa Coloma de Farners which is actually in Catalonia.

[26] Mirko Markovics (aka Jose Porra Spolea, Markovicz) was born in 1907 in Stijene, Podgorica, Montenegro. He was member of the Yugoslavian Communist Party and a graduate of a Soviet Russian military academy where he graduated with a Doctorate in Economics and received a commission in the Red Army. Markovics was sent to the U.S. to organize among Yugoslavian immigrants. He went to Spain from the U. S. He commanded the George Washington Battalion and briefly commanded the merged Lincoln-Washington Battalion during the Brunete campaign. Markovics returned to the U. S. after Spain, but was later deported to Yugoslavia. He died there in 1988.

Remembering Marcus Billings

Editor’s note: This is the first in a series of biographies of Lincoln Brigaders by Chris Brooks.

Marcus Judson Billings was born on June 10, 1914 in Redlands, California to O. S. Billings, a printer and the former Francis Devore, a housewife. He grew up in Redlands and graduated from Redlands High School.

After high school Billings enrolled in the University of California, Berkeley campus where he studied philosophy. He was a member of the Young Communist League.(1)

In early 1937, Billings volunteered for Spain and applied for a passport. He received his passport on February 19, 1937 and travelled across country to New York where he boarded the Washington sailing March 10, 1937 for France. Billings travelled from Le Havre, to Paris and then into Southern France. He made a night time crossing into Spain over the Pyrenees and enrolled in the International Brigades. (2)

Billings was assigned as a truck driver to the Intendencia in Albacete.(3) He was wounded on May 31, 1937 in the town of Almeria when German warships bombarded the town.(4) Billings’ unit was in the town delivering trucks. Three fellow drivers were killed in the shelling. 5) Billings suffered a leg wound and spent the remainder of his time in Spain in hospitals. He was treated in Almeria, Fortuna, Murcia and finally in a convalescent center near Valencia.(6) In early 1938 he was repatriated and returned to the US on February 23, 1938 aboard the Champlain.(7)

After returning Billings resumed his studies at UC Berkeley and graduated in 1938. After graduation he took a job as a social worker. He was active in the Veterans of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade. Due to his war wound he was unable to serve in WWII.(8)

In 1945 he married Margaret Cushwa. Together they raised three children Paul, born in 1950, Susan, born in 1954 and Alan born in 1957. Billings returned to UC Berkeley and earned a degree in Mechanical Engineering, graduating in 1948. (9) During the McCarthy era he was harassed by the FBI and dodged numerous subpoenas by the House Committee on Un-American Activities.(10)

Billings became a tool and die maker and was an active member of his trade union. In the 1970’s he purchased a small business producing handbags and managed it until he retired in the 1990s. Billings turned his business over to his son Alan. Billings died on November 5, 2009 in El Cerrito, California.(11)

(1) Adolph Ross Project, Survey Response, February 1995 (hereafter ARP Survey Response); Cadre List.

(2) SACB; Sail List; ARP Survey Response.

(3) It is not clear if the Intendencia had a distinct transportation unit or if their transport section was part of the AlbaceteAutoPark.

(4) German warships, including the pocket battleship Admiral Scheer, bombarded the town of Almeria at dawn on May 31, 1937. The warships fired more than two hundred shells destroying numerous buildings and wounding killing seventy civilians. Ostensibly the bombardment was a response to a series of Republican air raids that had damaged Italian and German ships in the harbor of the island of Mallorca and Ibiza.

(5) The three were:

Alex Alexander, 27 years old, listed his vocation as a driver, member of the CP joined in 1936, received Passport# 366586 issued on February 11, 1937, his address was listed as 2065 Dean Street, Brooklyn, New York; Sailed February 20, 1937 aboard the Ile de France; Arrived in Spain March 17, 1937, Served with the Albacete Auto Park, died June 5, 1937 Almeria hospital from wounds suffered in the shelling.

Ludwig Beregszaszy (Louis Beregszaszy), 32 years old, CP, received Passport# 29309279 issued on February 1937, listed his address as 107 124th Street, Richmond Hill, New York; Sailed March 10, 1937 aboard the Washington; Served with the AlbaceteAutoPark, died July 6, 1937 in a Hospital from wounds suffered in the shelling.

Jacob Lee Greenstein, b. Jamaica, Long Island, New York; 29 yrs of age, CP, received Passport # 366603 issued on February 11, 1937 listed his address as 117-07 107th Avenue, Richmond Hill, New York; Sailed March 10, 1937 aboard the Washington; Served with Albacete Auto Park, died June 5, 1937 in the Almeria hospital from wounds suffered in the shelling.

Arthur Landis (The Abraham Lincoln Brigade, p. 135) notes a fourth volunteer killed in the attack, Robert Chartrier. He noted his source as an April memorial article on the Albacete Auto-Park wall newspaper. Adolph Ross (American Volunteers in the Spanish Civil War, 1936-1939, p. 139) listed Chartrier as an unconfirmed volunteer> Ross noted that he consulted Hyman Chesler and Irving Goff who served in the Albacete Auto-Park..

(6) ARP Survey Response

(7) Ancestry.com

(8) ARP Survey Response

(9) ARP Survey Response

(10) Blake Green “The War They’ve Never Regretted” reprinted in The Volunteer, Volume 3, No. 4.

(11) ARP Survey Response; Ancestry.com

The making of the the Washington Battalion

Editor’s Note: This article is primarily constructed around a summary of three interviews that Sandor Voros conducted with Mirko Markovics in July 1937. An additional interview was planned that would have extended into the Brunete offensive but was never conducted as Markovics was called away and the interview never resumed.

Colonel Stephen Fuqua, David Doran and Captain Hans Amlie at Fuentes de Ebro, Nov. 1937 (Tamiment Library, NYU, 15th IB Photo Collection, Photo # 11-1350)

On April 24, 1937 Captain Mirko Markovics traveled to Madrigueras, site of one of the training bases of the International Brigades, to initiate the formation of a second American Battalion. (1) In Madrigueras Markovics found approximately 100 American volunteers. On first impression Markovics was an odd choice to take the command.

Born in 1907 in Montenegro, Markovics was an active member of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia. He had been selected to attend school in the Soviet Union where he received a doctorate in Economics from the Communist University for National Minorities of the West (KUNMZ). He was commissioned into the Red Army as a Commissar with the rank of Lieutenant. In 1936, he was sent to the United States where he headed the CPUSA’s Serbian Section and the Yugoslav Coordinating Bureau. Early in 1937, he volunteered for service in Spain and arrived there on April 20.

He found discipline among the volunteers lax. The prevailing attitude, he stated, was “We’re volunteers. If we want to accept orders and discipline, it’s ok. But if we do not like an order, we don’t have to carry it out. We have the right to decide what to obey and what to reject.” Markovics worked to instill greater discipline, advising the soldiers that they “must set an example and establish even better discipline than that of the loyalist army.” New volunteers, many of whom were Americans, arrived in Madrigueras from Albacete in batches of 25 to 30 a day. The newcomers accepted rules and regulations without question.

On April 30, Markovics received the official order to form a second American battalion. The following day, the men were organized into companies. Two days later, the International Brigade Headquarters formally appointed Captain Markovics as battalion Commander. Dave Mates, an American volunteer, was appointed Political Commissar. Markovics was not impressed by Mates who was a political appointee without military experience. He thought that Mates “did not mix well with the men,” noting he often failed to “show up” for the morning formation, and when he did, Mates was often “late and half dressed.”

Hans Amlie commanded the first company; Bill Halliwell, a Canadian emigrant from Britain commanded the second, and Alec Miller (also Canadian) the third (2). Due to prior military service in the United States—five years in the Army, two in the Marines–Amlie had originally been recruited by the American Socialist Party to lead the Debs Column.

Training began in earnest around May 10, 1937. Instructors and battalion officers conducted lectures and led practical exercises on topics such as scouting and marching. A foreign volunteer, identified as Rabele, provided much of the instruction. Markovics noted that the “best elements” were selected for the newly formed machine-gun company. Walter Garland, an African American veteran of Jarama, was made the company commander, supported by Milo Damjanovich, a Yugoslavian volunteer, as the Commissar.

On May 17, the Americans moved to the nearby town of Tarazona in order to enhance discipline. Markovics noted that in Madrigueras “drunkenness” was rife “especially among the French.” Initially, the citizens of Tarazona were not pleased to have the Americans because Franco-Belgian troops, who had been quartered in the town during the previous two months, had given the citizens a poor impression of internationals due to heavy drinking. The Americans eventually won over the townspeople.

Eight days after arriving, the battalion conducted its first field maneuvers. Despite some of the scouts becoming lost, the exercise was considered a success. General training continued with an emphasis on small arms, grenades, and machine-guns. The battalion also initiated some specialized training, including signals. At that point the battalion had approximately 400 men in training.

On June 4, International Brigade Headquarters designated the unit as the 19th Battalion of the XV International Brigade. The order specified a strength of 250 men. The next day, the battalion met in the town’s square and adopted George Washington as its name. The men initially wanted to name the battalion after Tom Mooney, a labor organizer imprisoned in California. They accepted the CP’s guidance delivered by telegram from the U.S. Communist Party in New York advising that naming the unit after Mooney “was not politically expedient at that time.” During the meeting a rumor circulated that the battalion would be going to the front and the men were “very happy.” Many considered themselves ready for action.

After two days without receiving an order to move, the men, though “very disappointed,” applied their attention to training. The biggest drawback to training was a lack of weapons. The battalion possessed only a Maxim machine gun, nicknamed “Mother Bloor,” and two light machine guns “stolen” for training purposes.

A watershed moment occurred during the parade formation on the morning of June 9. Captain Markovics addressed the men, saluted them and said “Salud Comrades!’” He was pleasantly surprised to see the men return his salute and hear their deafening response of “Salud!” Markowitz sensed that at that moment the men became “a regular army.”

The battalion’s leadership was solidified at this time and consisted of the following: Mirko Markovics Battalion Commander; Dave Mates Battalion Commissar; Hans Amlie Co. 1 Commander with Bernard Ames Co. Commissar; Edward Cecil-Smith Co. 2 Commander with Morris Wickman as Commissar; Hussera (Yardas) Co. 3 Commander with Harry Hynes as Commissar; Walter Garland MG Commander with Carl Geiser as Commissar. Kaye was listed as Intendant.

Battalion leaders planned a night maneuver on June 11 but plans were changed when the battalion received orders to move to the Jarama front. The men were eager to move. When the trucks arrived to move them to the front the men rapidly boarded along with their gear. Because fewer trucks arrived than anticipated the soldiers crowded 30 men to a truck.

After a painful overnight journey, the George Washington Battalion arrived “tired and hungry” in the town of Taracon around 11am on June 12. The movement order called for a brief stop to feed the troops and refuel the trucks. But the field kitchen truck broke down along the route and there was no back-up plan to feed the men. It became clear that insufficient preparations had been made. The unit was compelled to coerce “at the point of a gun” the local officials into providing gasoline for the trucks to complete their trip. They finally arrived at their destination, the town of Tailmer near Perales, about 2pm.

Insufficient preparations for the battalion’s arrival were further evident in Tailmer. The men found the town “overcrowded” with “empty stores” and no designated billets. The battalion staff obtained a stable for headquarters, while the men camped in the surrounding field. Markovics called up the division staff and “raised hell” for the poor work involved in the move. Division promised to send a kitchen. The truck arrived late that evening and the men were finally fed.

On June 16, the Washingtons were ordered to move into a second line position to replace the Dimitrov Battalion. The unit received arms from other battalions: “250 rifles, six heavy machine guns and two light machine guns.” The Washingtons were transported to Morata. Morale was “high” and the 280-man unit spent that night and the following day cleaning their weapons.