In the Jarama Series, The Volunteer Blog will present a series of articles examining the experiences of volunteers in the Abraham Lincoln Battalion from its formation to the Brunete Offensive in July 1937. Articles will focus both on the battalion’s formation as well as on the individuals who served. These articles are intended to provide the reader with a better appreciation of the men and women who made up the first American combat formation in Spain.

Jarama #15. Canadians in the Lincoln Battalion

The first Canadian volunteers for the International Brigades arrived in Cherbourg on January 28, 1937.[i] Nine additional volunteers arrived in the port on February 9, 1937.[ii] Almost all of these men joined the Abraham Lincoln Battalion. Canadian volunteers were integrated into the Lincolns from the onset. During the early days at Jarama, as many as forty Canadians served with the Lincolns and at least 11 were killed in action.[iii] Most Canadians served in Co. 2 at Jarama. By the summer, approximately 500 Canadians were in Spain despite the Canadian Foreign Enlistment Act passing in April 1937.[iv]

Canadians in Other Units

Because Canadians did not have a unit of their own at this point they served in numerous other formations. Approximately 30 Canadians served in the Washington Battalion. Washington BN commander Mirko Markovicks wanted to limit the number of Canadians in the Battalion because he was concerned that they would be transferred in the near future as the Canadians were pushing to form their own battalion.[v] Canadians Edward Cecil Smith and Edward Jardas both served as company commanders in the Washington Battalion Company.

Robert Kerr, the political representative for the Canadians, noted the following groups of Canadians serving in other formations in the fall of 1937:

- A company of Canadians in the Dombrovsky

- 45 Canadians in the Dimitroff at the Jarama front; may possibly have constituted a section of their own

- 45 Canadians in the Slavish artillery battery – battery G5A

- Others [served] in the Rakosi and in the Battalion Palafox.[vi]

![Canadians in Lincoln]()

Canadians in the Lincoln Battalion, Jarama 1937.

The Canadian Company

On June 5, 1937, forty Canadian volunteers transferred from the battalion of instruction at Tarazona to the Lincoln Battalion (Figure 1). They joined approximately ten Canadians already serving with the Lincoln Battalion. Battalion Pay records identify the men as the “Canadian Company.” Though it existed only briefly it stands as the first formal company-sized Canadian military formation in Spain.[vii] With the arrival of additional reinforcements prior to the Brunete Offensive, the Canadian Company became Section 3, of Company 3. Paddy O’Neil served as the section leader.[viii] On June 20, 1937 a total of 52 Canadians were serving with the Lincoln Battalion.[ix] The men reportedly called themselves the Mackenzie-Papineau Section.[x] The list is transcribed and placed in alphabetical order in Figure 1.

![Lincolns June 5]()

Figure 1. Members of the Canadian Company

Brunete

The Canadians in the Lincoln Battalion suffered heavy casualties during the Brunete Campaign. Five volunteers were killed during the attack on Villanueva de la Canada. Tom Bailey recalled that on the day after Villanueva de la Canada only twenty-one of the forty-man Canadian section were still in action.[xi] The section suffered additional casualties during the attack on Mosquito Ridge and ceased to exist when the Washington and Lincoln Battalions were merged.

The Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion

Even as the Canadians in the Lincoln and Washington Battalions entered action during the Brunete Campaign, new volunteers arriving at the training base pushed for the formation of a Canadian Battalion. The Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion was formally established in July 1937.[xii]

Sources

Hoar (Howard), Victor with Mac Reynolds. The Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion, The Canadian Contingent in the Spanish Civil War, Toronto: Copp Clarke, 1969.

Liversedge, Ronald, edited by David Yorke, Mac-Pap, Memoir of a Canadian in the Spanish Civil War. Vancouver: New Star Books, 2013.

Petrou, Michael. Renegades, Canadians in the Spanish Civil War, Vancouver and Toronto, UBC Press, 2008.

Library and Archives of Canada, Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion, Library and Archives Canada, PA-067118, Copyright: Expired. Photograph Collection, MIKAN ID.

Russian State Archive of Socio-Political History (RGASPI) ((Российский государственный архив социально-политической истории (РГАСПИ)); Records of the International Brigades (Comintern Archives, Fond 545).

Unpublished Biographical Dictionary by Myron Momryk.

Biographical database compiled by Michael Petrou.

[i] Russian State Archive of Socio-Political History (RGASPI) Fond 545, Opis 2, Delo 164, ll. 99, Point One of the Outline; These men are identified as: Thomas Becket, Frederick Lackey, Larry Ryan, Clifford Budgen, and Henry Beatie.

[ii] IBID. The men in the second group are identified as: Joseph Cambell, Joseph Glenn, Jack Steele, Michael Russel, Izzie Kupchik, George Cook, Tom Russel, Tom Michie and Joseph Leclerc.; Victor Hoar (Howard) and Mac Reynold, The Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion, The Canadian Contingent in the Spanish Civil War, (Toronto, Copp Clarke, 1969), 71. —Additional Canadians with the Lincolns include: Liege Claire, Adrian Van der Brugge, M. Waselenchuk, George Laskowsky, Joseph Campbell, Andrea Garcia, Michael Russell, Elias Aviezer, Nick Marinoff, Peter Johnson, and Arthur Morris. Hoar/Reynolds, 71 (Consensus)]

[iii] These include Thomas Beckett who was aboard the lost truck; Joseph Campbell, 2/27, Andres Menandes Garcia 2/27, Frederick D. Lackey 2/27, Yuri Liaskovsky 2/27, Clare Leige 2/27, Nick Marinoff 2/27, Jure Milijkovic 2/27, Thomas W. Mithcie 2/27, Arthur Walter Morris 2/27, and Michael Russell 2/27 (28). See Jarama Series The First Casualty and the Lost Trucks; and Pingarrón.

[iv] Michael Petrou, Renegades, Canadians in the Spanish Civil War, (Vancouver and Toronto, UBC Press, 2008), 11; Many Canadian volunteers were recent immigrants and were more comfortable serving in units where there native tongue was spoken.

[v] RGASPI Fond 545, Opis 2, Delo 164, ll. 59, Discussion with Bob Kerr, Canadian Political Commissar, Oct 19, 1937, Canadian Historical Commission.

[vi] IBID [Discussion with Bob Kerr, Canadian Political Commissar, Oct 19, 1937, Canadian Historical Commission, RGASPI Fond 545, Opis 2, Delo 164, ll. 59.

[vii] RGASPI Fond 545, Opis 3, Delo 504, ll. 60-61, and 82-83, Canadian Company Pay Records, June 10-20, and 20-30, 1937.

[viii] Petrou, Renegades, 69; Petrou states that Joseph Armitage was in charge of the section.; Hoar and Reynolds, The Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion; 86; Hoar quotes William Brennan who stated Tom Traynor was the commander with William Wilson as Commissar.

[ix] RGASPI Fond 545, Opis 6, Delo 537, ll. 2, List of Canadian Comrades, June 20, 1937; Note: John Nourm, Charles Parker, Joseph Turnbull and William Walsh from the June 5, 1937 Canadian Company rolls are not listed on this document. Those with an asterix were part of the Canadian Company in June. The list is transcribed and placed in alphabetical order below.

![Lincoln June 20]()

[x] Hoar and Reynolds, The Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion, 86

[xi] Petrou, Renegades, 68.

[xi] Ronald Liversedge, ed. David Yorke, Mac-Pap, Memoir of a Canadian in the Spanish Civil War, (Vancouver,New Star Books, 2013), See Chapter 2 for a first-hand account of the successful campaign to name the third American Battalion Mackenzie-Papineau.

Biographical data

American and Canadian volunteers served side-by-side during most of the Spanish Civil War. A biographical entry for each of the approximately 1,600 Canadian volunteers is being assembled.

Please note this is a work in progress.

Abbreviations/Acronyms

AFL = American Federation of Labor

b = Birth

BDE = Brigade

BN = Battalion

CPC = Communist Party of Canada

d = Death

KIA = Killed in action

MG = Machinegun

NUWSC = Currently unidentified union

OTOT = On to Ottowa Trek of 1935

POW = Prisoner of War

RNWMP = Royal Northwest Mounted Police

SUPA = Currently unidentified union

WIA = Wounded in action

WUL = Worker’s Unity League

YCL = Young Communist League

The Canadian Company

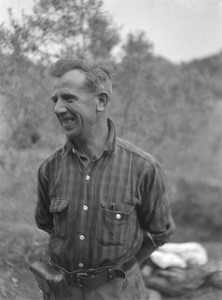

![Ambroziak]()

Peter Ambrozia in Spain, RGASPI Fond 545, Opis 6, Delo 541.

Ambroziak, Peter. (Petar; Ambrosiak; Ambroziac; Androziak; Abroziak); b. October 21, 1917, Montreal, Father Wasyl Ambroziak; Canadian, Ukrainian background; Attended primary school through 14 years of age; Single; Domicile Montreal; YCL 1936 (1934), Canadian Youth Organization, Workers Benevolent Association; To Spain March 8, 1937, was arrested entering Spain from France arrived April 22, 1937; Served with the XV BDE, Lincoln Battalion and Lincoln-Washington BN, Observer, rank Soldado; Auto Park; Served at Brunete, Quinto, Belchite, Fuentes de Ebro and Teruel; WIA Belchite in foot; Returned to Canada February 3, 1939; d. November 25, 2007, Ottawa, Ontario.

Sources: RGASPI Fond 545, Opis 6, Delo 541, ll. 31-35; Momryk; Petrou; Ancestry.

Bailey, Frank Thomas. (Tommy; Tom); b. January 8, 1901, Leicester, England; To Canada 1927; English; WWI veteran; Single; Salesman; Domicile Regina; Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan; CPC 1933 (1934), NUWSC London 1919, CP of Spain 1938; Left from Moose Jaw, via NY February 15, 1937; Arrived in Spain crossed mountains March 17, 1937; Served with the XV BDE, Washington BN; Lincoln-Washington BN; Mackenzie-Papineau BN; British BN; Transmissiones; Transport; rank Soldado; Served at Brunete, Aragon and Huesca; WIA; Sent to Disciplinary unit; Returned 1939.

Sources: RGASPI Fond 545, Opis 6, Delo 542, ll. 6-8; NAC, M-P Collection, Cecil-Smith, V. 1, F. 16, Memoirs and Accounts of Service in Spain, Bailey, Thomas, 46 pages, June 8, 1939; Momryk; Petrou.

Benham, Lionel. (Bunahm); b in Glace Bay, Nova Scotia; Domicile Vancouver, British Columbia; OTOT; Served with the XV BDE, Lincoln BN.

Sources: Momryk; Petrou.

Brown, William. (John; “Pop”); b. circa 1897; Canadian; WWI veteran; Domicile Windsor; Liberal Party; 41 years old; Arrived in Spain April 19, 1937; Served with the XV BDE, Lincoln and Lincoln-Washington BN, Postmaster; Served at Brunete, Belchite, Fuentes, Teruel Catalonia: Rank Sargento; Returned to Canada August 8, 1938.

Sources: RGASPI Fond 545, Opis 6, Delo 543, ll. 139; Petrou.

Budynkiewicz, Stefan. (Bodwich, Steve; Budenkewich; Budienkivich; Bovenewich; Budvich; Stepan; Stephen; Budynkevich, Stevans); b. February 21, 1907, Dubliany, Ukraine, To Canada 1928, Domiciled alien; Ukrainian; Construction Worker; Domicile Toronto, Ontario; CPC 1933; Arrived in Spain April 1937; Served with the XV BDE, Lincoln BN; Later with the Mackenzie-Papineau BN; Returned to Canada February 3, 1939; Mac-Pap Veterans Association (Toronto).

Sources: Momryk; Petrou.

Burke, Ainslie Puneo Lee. b. circa 1910, Sydney, Nova Scotia; Canadian; Father Edward Charles Burke, Mother Susan P. Burke; 8 years elementary and 2 years High School; No prior military service; Single; Clerk and Longshoreman; Domicile Toronto, Ontario; to US in 1935; CPC, OTOT; Arrived in Spain April 20, 1937 came in over the Pyrennes; Served with the XV BDE, Lincoln BN; Mackenzie-Papineau BN, Communications; Served at Brunete, Quinto, Belchite, Retreats; WIA September 1938; Returned to Canada September 26, 1938; WWII Canadian Army; Mac-Pap Veterans Association (Toronto); Visited Spain with Veterans Delegation in September 1979.

Sources: RGASPI Fond 545, Opis 6, Delo 543, ll.153-155; NAC, M-P Collection, Dent, V. 2, F. 16-17, Subject Files, Burke, Ainslie (Lee): Correspondence, research notes, and list of Mac-Pap veterans, 1977-85, & International Brigade travel document, correspondence, post card, and Empress of Britain brochure, 1937-38; Momryk; Petrou.

k-Carlson, Arvid. (Carlsen, Arvid; Arthur); b. circa 1909, Pittsburg, Pennsylvania; American; Finnish/ Swedish background; Single; Domicile Port Arthur, Ontario; CPC 1932; Arrived in Spain March 14, 1937; Served with the XV BDE; Medical service; WIA at Teruel, died of wounds in Murcia hospital January 1938.

Sources: List of Canadian Casualties in Spain MG30 E173 Vol.1 File 13; Momryk; Petrou.

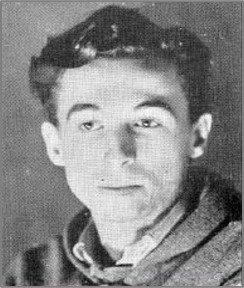

![Christy]()

Richard E. Christy of Vancouver, British Columbia, who was presumed killed in the retreats during the Spanish Civil War, 1936-1938. MIKAN 3213985

k-Christy, Richard E. (Christie; Christer); b. June 3, 1900, Vancouver; Canadian; Single; Logger; Domicile Vancouver; CPC 1934; Arrived in Spain April 29, 1937; Served with the XV BDE, Lincoln BN; Later with the Mackenzie-Papineau BN; MIA March 10, 1938, during the Retreats.

Sources: RGASPI Fond 545, Opis 6, Delo 544, ll. 65-68; Momryk; Petrou.

![Coleman]()

Lloyd Bryce Colman. (Coleman), of Vanguard, Saskatchewan., who was killed in action in Brunete during the Spanish Civil War. MIKAN 3214126

k-Coleman, Bryce Lloyd. (Coleman; Smith; Brice; Boyce; Charles); b. May 5, 1908, Vanguard, Saskatchewan; Canadian; Domicile Regina or Vanguard, Saskatchewan; Single; Farm and Ranch Worker; Co-operative Commonwealth Youth Movement, CPC, OTOT; Arrived in Spain March 17, 1937; Served with the XV BDE, Lincoln BN, one of forty Canadians transferred into the Lincolns on June 5, 1937, Section Commander; KIA July 6, 1937, Brunete.

Sources: List of Canadian Casualties in Spain MG30 E173 Vol.1 File 13; Americans and Canadians Killed in Spain Complete list to Nov. 15, 1937; RGASPI Fond 545, Opis 6, Delo 545, ll. 32 (Fiche only); NAC, M-P Collection, Hoar, V. 1, F. 10 Death and Disappearance Certificates, (7/6/37); Momryk; Petrou.

![Cowan]()

Wilfred Cowan (Cowen), December 1937; Harry Randall: Fifteenth International Brigade Films and Photographs; ALBA PHOTO 011; 11-0935, Tamiment Library/Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives, Elmer Holmes Bobst Library, 70 Washington Square South, New York, NY 10012, New York University Libraries

Cowan, Wilfred. (Wilf, Bill; Wolfort); circa 1917; English; Single; Painter and Longshoreman; Domicile 1577 Dundas Street, West Toronto, Ontario; YCL 1932; dropped out of party prior to leaving for Spain, YSULFTA; Arrived in Spain April 24, 1937; Served with the XV BDE, Lincoln BN June 10 until August 15; Intendencia August 15 to December 24, 1937; Transmissiones December 24, 1937 until February 22, 1938; Mackenzie-Papineau BN February 22, 1938 until April 1, 1938; 15th Corps Special MG BN, Co. 1 May 15, 1938 until October 3, 1938; Rank Cabo; Served at Brunete, Quinto, Belchite, Fuentes de Ebro, Huesca, Teruel, Seguro de los Baños; Retreats (Belchited-Gandesa), and Ebro Offensive; WIA 3 times twice in the chest and once in the head, July 11, 1937 Brunete, April 1, 1938 Gandesa, and September 24, 1938 Ebro, spent a total of three months in hospital; Returned to Canada 1939; WWII Canadian Army; Mac-Pap Veterans Association (West).

Sources: RGASPI Fond 545, Opis 6, Delo 545, ll. 67-74; Petrou.

Csirmaz, Mihaly. (Czirmas, Mike; Csizmzr; Czirmaz; Csirmos; Cairmay; Michael, Mike); b. circa 1902, Hungary, To Spain 1929; Hungarian; Farm Worker; Domicile Montreal; CPC 1934; To Spain April 1, 1937; Served with the XV BDE, Lincoln BN; Returned to Canada December 18, 1938.

Sources: RGASPI; Momryk; Petrou.

Cunningham, George. b. December 30, 1912, Cowdenbeath, Scotland, To Canada 1929; Scottish; POW; Salesman; Domicile Toronto, Ontario or Milton, Ontario; To Spain February 2, 1937, travelled on Canadian Passport; Served with the XV BDE, Lincoln BN; Then to British BN where became company commissar; Attended Commissar’s school starting November 29, 1937; Served at Jarama, Brunete, Quinto, Belchite, Fuentes de Ebro; Captured March 25, 1938, Gandesa, during the Retreats, San Pedro de Cardenas; Exchanged April 5, 1939; Returned to Canada May 6, 1939; Mac-Pap Veterans Association (Toronto).

Sources: List of Canadian Casualties in Spain MG30 E173 Vol.1 File 13 (Captured); RGASPI Fond 545, Opis 6, Delo 545, ll. 110; Geiser; Momryk; Petrou.

Freeze, _____. Currently unidentified. Possibly Herman Fries who is normally identified as an American volunteer.

Fries, Herman. (Frye, Herman), b. September 18, 1908, Keenigeberg, Germany; German American; Single; Electrician; CP 1932 and Spanish CP; Domicile 338 East 15th Street, NYC; Sailed April 5, 1937 aboard the Britannic; Arrived in Spain on April 29, 1937; Served with the XV BDE, Washington BN; WIA July 9, 1937 Brunete; After recovery served as an electrician in a hospital; Rank Cabo.

Sources: Cadre; RGASPI.

![Goguen]()

Emil Goguen in Spain. RGASPI, Fond 545, Opis 6, Delo 549

Goguen, Emil. (Gougen; Gouguen; Emile; Frenchy); b. January 7, 1900, Cape Bald New Brunswick; Domicile Vancouver; Cape Bald (New Brunswick?); French Canadian; Father Placid Gougen, Mother Clonid Gouguen; Primary and Elementary school education; WWI Canadian Army 1915, 66 and 57th Infantry Regiments and RNWMP; Single; Telegrapher, Construction Worker and Logger; CPC 1932, applied for CP of Spain, LWIU CIO, former member IWW; Arrived in Spain April 15, 1937, travelled on Canadian passport; Served with the XV BDE, Lincoln BN; Lincoln-Washington BN, Later with 35th battery, 4th Group Artillery, Anti-Tank A-A, Rank promoted to Cabo August 1937 and Sargento February 11, 1938; Served at Brunete, Quinto,, Aragon, Teruel, Castellon, Levante; WIA August 24, 1937 and June 10, 1938; WWII Canadian Army

Sources: RGASPI Fond 545, Opis 6 Delo 549, ll. 82-86; Momryk; Petrou.

![Grant]()

Grant, Lewis Charles. POW. MIKAN 3216232

Grant, Lewis Charles. (Scotty); b.circa 1889, Scotland; Scottish; WWI British Army; Domicile Calgary, Vancouver; Single; CPC 1937; Served with XV BDE, Lincoln BN; Later with a Medical Unit; WIA Belchite; Returned in 1939, possibly to England.

Sources: RGASPI Fond 545, Opis 6, Delo 550, ll. 14; Momryk; Petrou. [This may not be the correct Grant]

Handziuk, Nick. (Hanzuk, Polad; Hanzuik; Hanziuk; Mykola; Nikolaj); b.circa 1899, Ukraine, To Canada 1927; Ukrainian; Married, 3 kids; Miner; Domicile Toronto, Ontario; CPC 1935; Arrived in Spain May 20, 1937, travelled on a Polish Passport; Served with the XV BDE, Lincoln BN; Later at Tarazona and prison guard at Castell de Fels (Castillo); Returned to Canada 1939.

Sources: RGASPI Fond 545, Opis 6, Delo 551, ll. 35 (fiche only); Momryk; Petrou.

![Janei]()

Jenei Gabor. (Jeney), of the Abraham Lincoln Bn. was killed on 17 July, 1937 at Brunete, during the Spanish Civil War, 1936-1938. MIKAN 3217136

k-Janei, Gabor. (Jeney; Jenei; Yaney; Jonci; Jency; Genei; Jenel, Gabriel); b. circa 1901, Hungary, To Canada 1927; Hungarian; Single; Blacksmith; Domicile Timmins or Hamilton, Ontario; CPC 1932; Arrived in Spain April 25, 1937; Served with the XV BDE, Lincoln BN; Badalona; KIA July 20, 1937, Brunete (alt. July 17, 1937 or September 20, 1937 Belchite).

Sources: List of Canadian Casualties in Spain MG30 E173 Vol.1 File 13; NAC, M-P Collection, Hoar, V. 1, F. 10 Death and Disappearance Certificates, under Jeney, Cabor (7/20/37); RGASPI Fond 545, Opis 6, Delo 554, ll. 23 (fiche only); Momryk (under Jenel); Petrou.

k-Kane, James. (Kam; “Scotty;” Jimmie; Jim); b. circa 1902; Domicile Toronto, Ontario; CPC, Longshoreman’s Union; In Spain in June 1937; Served with the Lincoln BN; KIA July 6, 1937, Brunete.

Sources: List of Canadian Casualties in Spain MG30 E173 Vol.1 File 13; Americans and Canadians Killed in Spain Complete list to Nov. 15, 1937; RGASPI Fond 545, Opis 6, Delo 555 ll. 21 (fiche only); Momryk; Petrou.

![Koster]()

Kostur of Port Arthur, Ontario, who was presumed killed in the Retreats during the Spanish Civil War, 1936-1938. MIKAN 3217856

k?-Koster, William. (Kostur; Kostar); b. circa 1906, Poland, To Canada 1923; Ukrainian; Single; Baker; Domicile Sunderland, Ontario; Port Arthur, Ontario; CPC 1934; Arrived in Spain May 20, 1937; Served with the XV BDE, Lincoln BN; Reported MIA/POW April 3, 1938; Fate uncertain.

Sources: List of Canadian Casualties in Spain MG30 E173 Vol.1 File 13 (W. Kostur, MIA April 1938); RGASPI Fond 545, Opis 6, Delo 556, ll. 65 (fiche only under Kostur, William); Momryk; Petrou.

Levitt, Ralph. (Leavitt); In Spain June 20, 1937; Served with the XV BDE, Lincoln BN.

Sources: Momryk; Petrou.

![Mangel]()

David Mangel of Toronto, Ontario MIKAN 3358146

Mangel, David. (Mengel); b. September 10, 1900 (October 9), Borisow, Poland, To Canada 1920; Jewish; Single; Painter; Domicile Toronto, Ontario and Montreal, Quebec; CPC 1925, Brotherhood of Painters, Local Secretary; WUL, AFL; To Spain February 20, 1937; Arrived in Spain May 25, 1937 (arrested and jailed in France on the way); Served with the XV BDE, Lincoln BN; Later with the 35th Anglo American Battery; WIA at Brunete and again at Quinto; Rejected by COL O’Kelly; Held in French Internment Camps; Fought in the Israeli War of Independence 1948 and remained in Israel.

Sources: NAC, M-P Collection, Cecil-Smith, V. 1, F. 16, Memoirs and Accounts of Service in Spain, Mangel, David, 3 pages, no date; RGASPI Fond 545, Opis 6, Delo 558, ll.44-45; Momryk; Petrou; Polek Hurrah Revolutionaries and Polish Patriots.

![Martinuk]()

Martiniuk of Winnipeg, Manitoba MIKAN 3358220

k-Martinuk, Anton. (Martinuik; Martyniuk; Martinyuk; Marteniuk; Antonio; Anthony; Tony; John); b. circa 1906, possibly born in Poland; Ukrainian; Miner and Foundry Worker; Domicile Winnipeg, Manitoba or Toronto, Ontario; No Party; Arrived in Spain May 22, 1937; Rank Soldado; Served at Brunete and Aragon; KIA February 1938.

Sources: List of Canadian Casualties in Spain MG30 E173 Vol.1 File 13; RGASPI Fond 545, Opis 6, Delo 558, ll. 79-81; Momryk; Petrou.

![McClure]()

Alexander C. McClure of Montreal, P.Q., who was killed at Fuentes de Ebro, during the Spanish Civil War, 1936-1938. MIKAN 3218578 [from a group photo – looks like Cecil-Smith];

k-McClure, Alexander Crocher. (MacClure; McLure, Alex); b. circa 1909; New Zealand; Mining Student; Domicile Montreal, Quebec; Arrived in Spain March 28, 1937; Served with the XV BDE, Lincoln BN; KIA October 13, 1937, Fuentes de Ebro.

Sources: List of Canadian Casualties in Spain MG30 E173 Vol.1 File 13 (10/10); Americans and Canadians Killed in Spain Complete list to Nov. 15, 1937; RGASPI Fond 545, Opis 6, Delo 559, ll. 24 (fiche only); Momryk (under MacLure and McClure); Petrou.

![McGrath]()

John Freeman McGrath in Spain, RGASPI, Fond 545, Opis 6, Delo 559.

McGrath, John Freeman. b. March 28, 1905, Chatham New Brunswick; Canadian, Irish background; Father Valentine McGrath; Elementary school education; Single; Lumber Worker; Domicile Edmonton, Alberta; CPC December 1934, SUPA; applied for Spanish CP but denied; Arrived in Spain April 20, 1937; Served with the XV BDE, Washington BN, Co. 2 in training at Madrigueras to the front with the Lincoln BN, Sanidad; Later with Mackenzie-Papineau BN; Sanidad Stretcher bearer; Rank Cabo; Served at Brunete, Quinto, Belchite, Mevidiana [?], Funetes, Teruel, Gandesa, Ebro; Returned to Canada 1939.

Sources: RGASPI Fond 545, Opis 6, Delo 559, ll. 61-69; Momryk; Petrou.

McLaughlin, Michael P. (Bill); Domicile Hamilton; CPC 1935; Served with the XV BDE, Lincoln BN; Later with the Mackenzie-Papineau BN; WIA; Returned to Canada July 1938.

Sources: RGASPI Fond 545, Opis 6, Delo 559, ll. 100; Momryk; Petrou.

Miller, John. (Millar; Jock); b. June 20, 1898, Glasgow, Scotland; Scottish; WWI veteran; Single; Painter; Domicile Windsor; CPC 1933; Arrived in Spain April 24, 1937; Served with the XV BDE, Lincoln BN; Later with the Mackenzie-Papineau BN, Section leader at Brunete later promoted to company commander; Served at Brunete, Fuentes de Ebro, Teruel; WIA at Brunete and Pandols; Rank Teniente; Later worked in the BDE Service de Personnel; Spoke English, French, German, Rumanian, Spanish and Yiddish; Returned 1939.

Sources: RGASPI Fond 545, Opis 6, Delo 560, ll. 57-64; Momryk; Petrou.

Moffitt, Arthur. (Moffat; Muffit; Muffet; Moffatt; Art); b. September 15, 1905, Newcastle, England; English; Miner, Logger and Construction Worker; Domicile Edmonton, Vancouver; YCL 1931 (CPC 1929), United Mine Workers of America; Arrived in Spain April 20, 1937; Served with the XV BDE, Lincoln BN; Later with the John Brown Battery; WIA Brunete July 6, 1937; Returned to Canada February 11, 1939.

Sources: RGASPI Fond 545, Opis 6, Delo 560, ll. 83-84; Petrou.

Morrow, William. (Morran; William; Morron; Kane; Bill); b. circa 1901, Glasgow, Scotland; Scottish; Single; Miner and Dock Worker; Domicile Hamilton; CPC 1933; Arrived in Spain April 29, 1937; Served with the XV BDE, Lincoln BN; Later with the Mackenzie-Papineau BN; Served at Jarama and Badalona; injured leg in accident; Declared fit for rear service; Returned to Canada October 29, 1938.

Sources: RGASPI Fond 545, Opis 6, Delo 560, ll. 112; Momryk; Petrou.

![Norum]()

John A. Norum of Winnipeg, Manitoba, who was killed at Belchite during the Spanish Civil War, 1936-1938. MIKAN 3219495

k-Norum, John. (Norrum); b. circa 1902, Norway, To Canada 1929; Norwegian; Laborer; Domicile Winnipeg, Manitoba; Arrived in Spain March 17, 1937; Served with the XV BDE.; WIA September 1937 in Belchite, died in hospital.

Sources: List of Canadian Casualties in Spain MG30 E173 Vol.1 File 13; Momryk; Petrou.

![O'Neal]()

Stewart “Paddy,” (Stewart Homer)O’Neil, , of Vancouver, British Columbia, who was in the Mackezie-Papineau Bn. and was killed at Brunete, during the Spanish Civil War, 1936-1938. MIKAN 3219595

k-O’Neal, Paddy (Homer, Stewart O’Neal; Paddy O’Neil; Stuart); b. December 18 (28), 1900, Ireland, To Canada 1928; Irish; WWI British Army, 1917-26, France, India, and Mesopotamia; Lumber Worker and Organizer; Domicile Vancouver, Toronto, Ontario; CPC, OTOT; Expelled from Canada due to political activity; To Spain from England. Arrived in Spain March 30, 1937; Served with the XV BDE, Lincoln BN, Co. 3, Section 3; Section Leader, Canadian Section at Brunete (says March 7, 1938 Volunteer for Lib.), Rank Sargento; KIA July 6, 1937, Brunete.

Sources: Americans and Canadians Killed in Spain Complete list to Nov. 15, 1937 (under O’Neil); List of Canadian Casualties in Spain MG30 E173 Vol.1 File 13 (lists city and province as Vancouver, BC); RGASPI Fond 545, Opis 6, Delo 562, ll. 33 (Fiche only under O’Neil); McLoughlin (under O’Neil); Momryk; Petrou.

![Parker]()

Charles. (George), Parker of Vancouver, British Columbia, who fought in the Spanish Civil War, 1936-1938 and was killed at Quinto. MIKAN 3219722

k-Parker, Charles. (Chuck; George); b. circa 1901, England, To Canada 1929; English; Sports Instructor; Domicile Vancouver, British Columbia; Winnipeg; CPC; In Spain June 20, 1937; Served with the XV BDE, Lincoln BN; Lincoln-Washington BN, led Canadian section at Brunete; KIA August 24, 1937, Quinto (September 28, 1937). Was a legendary “footballer” in British Columbia.

Sources: List of Canadian Casualties in Spain MG30 E173 Vol.1 File 13; Americans and Canadians Killed in Spain Complete list to Nov. 15, 1937; Momryk; Petrou.

![Peters]()

Robert James Peters of Toronto, Ontario, who fought in the Spanish Civil War, 1936-1938

MIKAN 3220020, 3220021

Peters, Robert James. b March 28, 1915, Wales, To Canada 1931; Single; Sailor; Domicile Toronto; CPC 1936, Canadian Seamen’s Union; Arrived in Spain April 2, 1937; Served with the XV BDE, Lincoln BN; Mackenzie-Papineau BN; British BN; WIA July 7, 1937, Brunete; transferred mail service Auto Park as a motorcycle dispatch rider; Returned 1939; Returned to Wales; Note: Peters states he transferred to the British Battalion and makes no mention of his time in the Lincolns in his memoir.

Sources: RGASPI Fond 545, Opis 6, Delo 563, ll. 99; Momryk; Petrou; Greg Lewis, A Bullet Saved My Life.

Schofield, Ronald. (Schoefield; Schomberg; Ron); b. December 26, 1912, Rochdale, England, To Canada 1928; English; Single; Baker; Domicile 38 Tiverton Avenue, Toronto; CPC 1935; Arrived in Spain April 6, 1937; Served with the XV BDE, Lincoln BN, Co. 1, June 10, 1937; Transferred to 35th Division July 13, 1937; Hospital Castillegeco October 2, 1937 until January 15, 1938 working as cook and store keeper; Battalion of Instruction January 30, 1938 until February 15, 1938,; then to the Mackenzie-Papineau BN February 15, 1938 through 2nd Gandesa; Last unit 35th Division Zapadors until October 1, 1938; Soldier, Cook and Stretcher Bearer; Rank Soldado; Served at Brunete, Athera, Alcaniz, Gandeza, Ebro Offensive (Pandols); WIA July 6, 1937, Villanueva de la Canada, Brunete; To England via Cerbere December 19, 1938; To Canada April 16, 1939; Mac-Pap Veterans Association (1977).

Sources: RGASPI Fond 545, Opis 6, Delo 568, ll. 77-85; Momryk; Petrou.

Schmeltzer, George. (Sohmeltzer, George; Smeltzer; Schmetzer; Gyorgy); b. February 7, 1902, Lajos-Komaro, Hungary, To Canada 1927; Hungarian; Domicile Toronto; Montreal; Arrived in Spain March 23, 1937; Served with the XV BDE, Lincoln BN; Rejected by Col O’Kelly; Returned to Canada May 20, 1939.

Sources; Momryk; Petrou.

k-Skinner, Baden A. (Taffy; Terry); b. May 20, 1900, Tredegar, Wales, To Canada 1928; Welsh; Single; Miner; Domicile Vancouver; CPC 1935; Arrived in Spain May 18, 1937; Served with the XV BDE, Lincoln BN; Later with the Mackenzie-Papineau BN; KIA September 23, 1938, Ebro Offensive.

Sources: Momryk; Petrou.

Steer, George. (Speer); b. circa 1900, London, England, To Canada 1925; English; WWI British Army, served in Russia and Canadian Army; Married, 3 kids; Tailor and Canadian Army; Domicile Chatham, Toronto, Alberta; CPC 1933; Arrived in Spain May 14, 1937; Served with the XV BDE, Lincoln BN; Later with the Mackenzie-Papineau BN; WIA on July 6, 1937 and again on September 21, 1938; Returned to Canada 1939; In January 1938 he was in hospital at Mahora and requested repatriation.

Sources: RGASPI Fond 545, Opis 6, Delo 570, ll. 59-60 (letter); Momryk; Petrou.

Traynor, Thomas. (Trainor; Trayder; Traymor; Paddy); b. June 5, 1897, Derry (Monaghan or Tyronne), Ireland, To Canada August 9, 1925, Naturalized Canadian; Irish; Single; Time Keeper and Laborer; Domicile Toronto; CPC 1936; Travelled on Canadian Passport #32251; Arrived in Spain April 24, 1937; Served with the XV BDE, Lincoln BN, Co. 3, “Canadian” Section 3, Section leader after Paddy O’Neil was killed at Brunete on the second two; WIA at Mosquito Ridge, Brunete, in hospital; Mackenzie-Papineau BN, rose to Section Leader, Fuentes de Ebro and Teruel; Returned to Canada October 29, 1938.

Sources: RGASPI Fonod 545, Opis 6, Delo 572, ll. 64-69; McLoughlin; Momryk; Petrou.

Turnbull, Joseph Aubrey. (Trunbell; Jose); b. September 1, 1915 Grand Valley Ontario; Canadian; Parents Joseph Wesley and Luella Pear (Adams) Turnbull; Public School; Canadian Militia, 1 year, Algonquin Rifle, 1931; Single; Seaman, Relief Camps, Construction, and Post Office; Domicile 278 Augusta Avenue, Toronto, and Guelph, Ontario, transient; CPC 1936, Canadian Seaman’s Union, AFL; To Spain April 28, 1937; Crossed the Pyrenees; Served with the XV BDE, Washington BN in training transferred to the Lincoln BN; Canadian Section; Cabo, WIA Brunete; Censor in post office after August 1937; Served At Villanueva de la Canada, Quijorna, and Misquito Hill; Returned to Canada sailing from Liverpool on January 27, 1939 aboard the Duchess of Richmond; WWII A Squadron, 12th Canadian Army Tank Regiment, Canadian Overseas Army, Mediterranean; d. 1993.

Sources: RGASPI Fond 545, Opis 6, Delo 572, ll.45-84; Momryk; Petrou; Easterbrook.

Walsh, William Francis. b. May 18, 1911, London, England; English; Single; Pipe Fitter; Domicile 164 Alameda Avenue, Toronto, Ontario; YCL, CPC 1937; Served with the XV BDE, Lincoln BN, Co. 1; Served at Brunete, Quinto, Belchite, Fuentes de Ebro, and Ebro Offensive; WIA July 6, 1937, Brunete and again August 1, 1938, Ebro; Rank Sargento; In November 1938 he was in hospital awaiting repatriation; Returned to Canada 1939.

Sources: RGASPI Fond 545, Opis 6, Delo 575, ll. 1-8; Momryk; Petrou.

k-Wilson, William. (Bill); b. January 9, 1901, Scotland; Scottish; Farm Worker (tractor driver); Domicile Calgary; CPC; Arrived in Spain May 15, 1937; Served with the XV BDE, Lincoln BN; Political Commissar of Canadian Section, Brunete; MIA April 3, 1938.

Sources: RGASPI Fond 545, Opis 6, Delo 575, ll. 104 (fiche only); Momryk; Petrou.

Others Canadians already serving with the Lincoln Battalion

![Armitage 1]()

![Armitage 2]()

Joseph Albin Armitage of Vancouver. British Columbia, who was killed at Brunete, during the Spanish Civil War, 1936-1938 MIKAN 3214528; Section Leader, Armitage kneeling third from the right with his section just before the Brunete Offensive. Oscar Bloom is far right front row.

k-Armitage, Joseph. (Albin; Allen; George; Joe; Tom); b. circa 1902; Scottish or English; WW I veteran; Coal Miner; Domicile Vancouver; CPC 1933; Arrived in Spain March 17, 1937; Served with the XV BDE, Lincoln BN, Section Leader; KIA July 6, 1937, Villanueva de la Canada, Brunete.

Sources: RGASPI Fond 545, Opis 6, Delo 541, ll. 85-86 (Fiche only); Americans and Canadians Killed in Spain Complete list to Nov. 15, 1937; List of Canadian Casualties in Spain MG30 E173 Vol.1 File 13; Momryk; Petrou.

Bedard, Joseph Thomas. b.circa 1895, Hawkesbury, Ontario; French Canadian; WWI veteran; Construction Supervisor; Domicile Hawkesbury, Ontario, Montreal; CPC 1932; To Spain January 8, 1937; Returned to Canada October 12, 1937.

Sources: RGASPI Fond 545, Opis 6, Delo 542, ll. 66 (Fiche only); Momryk; Petrou.

![Bloom]()

Jean Oscar Bloom, who was in the Abraham Lincoln Bn. and died at Brunete during the Spanish Civil War, 1936-1938. MIKAN 3212765;

k-Bloom, John Oscar. (Blum; Asselson; Alms; Orville; Oselson; Orville; Jean; “Red”); b. circa 1913; Militia possibly with Calgary Regiment; Domicile Edmonton; YCL/CPC 1933; Arrived in Spain February 16, 1937; Served with the XV BDE, Lincoln BN; KIA July 6, 1937, Brunete.

Sources: RGASPI Fond 545, Opis 6, Delo 543, ll. 41 (fiche only); Americans and Canadians Killed in Spain Complete list to Nov. 15, 1937; List of Canadian Casualties in Spain MG30 E173 Vol.1 File 13; Momryk; Petrou.

Cochrane, Thomas. (Cochrane; “Pop”); b. December 10, 1885, Belfast, Ireland; Irish; No prior military service; Married, 6 kids; Electrician (Auto Worker); Domicile Windsor, Ontario; CPC, National Unemployed Association; To Spain May 28, 1937; Served with the XV BDE, Lincoln BN, WIA Brunete (WIA September 6, 1937); Later in Valencia with Censor (mail service); Repatriated; Arrived in Toronto on September 6, 1938.

Sources: RGASPI Fond 545, Opis 6, Delo 545, ll. 4-10; McLoughlin; Momryk; Petrou.

k-Deck, John. (Deek); b. circa 1904; German; US Army Cavalry; Marine Engineer; Domicile New Westminster or Vancouver, British Columbia; No Party, International Seaman’s Union; To Spain December 5, 1936; Served with the XV BDE, Lincoln BN; Chief Scout; Adjutant to chief of staff; KIA July 9 (10), 1937, Brunete.

Sources: List of Canadian Casualties in Spain MG30 E173 Vol.1 File 13; Americans and Canadians Killed in Spain Complete list to Nov. 15, 1937; RGASPI Fond 545, Opis 6, Delo 546, ll. 26-27; Momryk; Petrou.

![Dent]()

Walter Dent. Advance, May 1937.

Dent, Walter Everett. b. 1917, Parry Sound, Ontario; Canadian, Irish protestant background; Second Form, in HS then had to leave and get a job; No prior military service; Carpenter; Domicile Everett, Parry Sound, Toronto, Ontario; YCL and CPC 1936; To Spain February 18, 1937; Recommended for officers school by Merriman; Mackenzie-Papineau BN?; WIA February 27, 1937; back with unit in October 1937; Awarded IB medal January 24, 1939; WWII British Army; MacPap Veterans Association (Toronto).

Sources: NAC, M-P Collection, Cecil-Smith, V. 1, F. 16, Memoirs and Accounts of Service in Spain, Dent, Walter, 9 pages, no date; NAC, M-P Collection, Dent, V. 2, F. 5, Subject Files, Dent, Walter: General Correspondence, Veterans of the Mackenzie-Papineau BN, 1977-1984, National Office correspondence, Veterans of the Mackenzie-Papineau BN, 1977-1985, & Reminiscences of the SCW (transcript of an interview), 1980; RGASPI Fond 545, Opis 6, Delo 546, ll. 38-39; Momryk; Petrou.

Halliwell, William. (Holliwell; Halawell; Hiliwell; Hollowell; John); b. circa 1894, Preston, England, To Canada 1929; English; WWI British Army 6 years; Machinist; Domicile Edmonton; Vancouver; Anti-Fascist; To Spain March 1, 1937; Served with the XV BDE, Lincoln BN March 16, 1937; Washington BN, Co. Commander; Rank Alferez May 5, 1937; Teniente August 1, 1937; Rank Soldado; Served at Jarama, Brunete, Belchite, Quinto, Belchite, and Gandesa; WIA July 8, 1937 and again August 24, 1937 at Belchite; later with Mackenzie-Papieneau BN; and instructor; Rank Tiente; Returned to Canada October 1937.

Sources: RGASPI Fond 545, Opis 6, Delo 551, ll. 35, 45; Momryk; Petrou.

Hayes, George. b. circa 1896; WWI veteran; Building Worker and Miner; Anti-Fascist; Domicile Portage Avenue, Winnipeg, Canada; Arrived in Spain March 17, 1937 via NY; Served with the XV BDE, Lincoln BN; Mackenzie-Papineau BN; Auto Park; Served at Jarama and Brunete; Returned to Canada April 23, 1939.

Sources: RGASPI Fond 545, Opis 6, Delo 551, ll. 75; Momryk; Petrou.

Kelly, Joseph. (Kelley; Joe); b. April 2, 1900 (March 10, 1898), Belfast, Ireland, Naturalized Canadian.; Irish; WWI veteran later in IRA; Single; Miner, Lumber Worker, and Trade Union Organizer; Domicile Vancouver; CPC 1932; Arrived in Spain February 14, 1937; Served with the XV BDE, British BN; Lincoln BN, Co. 3; military instructor; also front line service; Rank Teniente November 1937; Served at Jarama, Brunete, Belchite, and Caspe; WIA July 13, 1937, Brunete, in Madrid Hospita from July 13 until August 17, 1937; Later injured in an accident at the Training Base; Returned to Canada February 3, 1939; d. January 2, 1977, Kamloops, British Columbia.

Source: RGASPI Fond 545, Opis 6, Delo 555, ll. 40-47; McLoughlin; Momryk; Petrou.

Kristiansen, Kristian. (Kristian; Kristerson; Kristensen; Krist; Kriss; Emanuel; Emmanuel; Emanual); b. circa 1894, Norway; Norweigan; Divorced, 2 kids; Carpenter; Domicile Vancouver; CPC 1934, section organizer; Arrived in Spain March 14, 1937; Served as an Armourer; Returned to Canada September 1938.

Source: RGASPI Fond 545, Opis 6, Delo 556, ll. 98; Momryk; Petrou.

Lapschuk, Myroslaw.(Lapchuk; Lapckuk; Kennedy; Maurice; Morry; Morris);b. January 13, 1913 (1912), Montreal; Canadian, Ukrainian background; Married in Spain; Cook; Domicile Montreal; YCL 1934; To Spain March 12, 1937; Served with the XV BDE, Lincoln BN; Casa de Prevencion; Republican authorities would not let his wife leave the country; Returned to Canada February 1939.

Source: RGASPI Fond 545, Opis 6, Delo 557, ll. 11; Momryk; Petrou.

Latulippe, Lucien. (Lattilupe); b. June 28, 1908, Montford, Quebec; French Canadian; Canadian Militia; Single; Painter worked at hospital; Domicile 4159 Rivard Street, Montreal; Montford, Province Quebec; CPC 1936; To Spain February 6, 1937; Arrived at front on February 17, 1937; Served with the XV BDE, Lincoln BN, MG Co., runner; Rank Soldado; Became seriously ill and was sent to rear, worked in the Post Office; Apparently sent back to the front; Broke down at front, Sick February 4, 1938 and proposed for repatriation; Deserted? Returned to Canada on May 31, 1938 “on his own.”

Source: RGASPI Fond 545, Opis 6, Delo 557, ll. 13; Momryk; Petrou.

Miller, Allan. b. March 31, 1912, Scotland; Scottish, 2 years High School; 2 years Cadet Corps held rank of Captain; Single; Miner and Clerk at Eaton; Domicile Toronto; CPC 1932 (19310; Arrived in Spain March 12, 1937 via NY; Served with the XV BDE, Lincoln BN and Mackenzie-Papineau BN; Rank Sargento; Served at Jarama, Brunete and the Aragon; WIA May 24, 1938; Returned to Canada September 1938; MacPap Veterans Association; d. December 20, 1983.

Source: RGASPI Fond 545, Opis 6, Delo 560, ll. 56; Momryk; Petrou.

![Neilson]()

Peter Sorin Neilson of Vancouver, British Columbia, who was in the Abraham Lincoln BN. and was presumed killed in the Retreats, during the Spanish Civil War, 1936-1938

k?-Neilson, Peter Sorin. (Nielson, Neilsen); b. June 27, 1897, Denmark, To Canada 1916; Danish; left school before age 11 to work; Single; Logger and Laborer; Domicile Vancouver, transient; CPC 1933, AFL, IWW, OTOT; Arrived in Spain April 29, 1937; Served in the XV BDE, Lincoln BN; later with Mackenzie-Papineau BN; Rank LT (was in officers’ school); WIA January 16, 1938; MIA April 3, 1938, Survived (per Momryk).

Source: NAC, M-P Collection, Cecil-Smith, V. 1, F. 16, Memoirs and Accounts of Service in Spain, Nielson, Pete, 2 accounts, 4 pages, no date; RGASPI Fond 545, Opis 6, Delo 561; ll. 17 (fiche only); Momryk; Petrou.

![Paivo]()

Jules Pekka Paivo, internet.

Paivio, Jules Pekka. (Koponen, Pauli; Airio); b.April 30(29), 1917, Ware TWP, Ontario; Finnish; POW; Single; Clerk; Canadian, Finnish background; Domicile Sudbury, Mattawa, Ontario; YCL 1930, (CP 1935) joined CP in Spain; Arrived in Spain March 13, 1937; Served with the XV BDE, Lincoln BN; Mackenzie-Papineau BN; OTS; Rank Teniente; Served at Jarama from April to June; Brunete; Then to OTS, remained at Tarazona after OTS as Topography Instructor; Captured April 1 (4), 1938; San Pedro de Cardenas; Exchanged April 5, 1939; Returned to Canada May 6, 1939; WWII Canadian Army; MacPap Veterans Association (Toronto); Visited Spain with Veterans Delegation September 1979; d. September 4, 2013; Last surviving Canadian Combat veteran.

Sources: List of Canadian Casualties in Spain MG30 E173 Vol.1 File 13 (Captured April 1938); NAC, M-P Collection, Hoar, V. 1, F. 9, Accounts of Experiences in Spain, 1939; RGASPI Fond 545, Opis 6, Delo 563, ll. 12; Geiser; Momryk; Petrou, Obituary, Toronto Star, September 13, 2013. http://www.legacy.com/obituaries/thestar/obituary.aspx?pid=166936459

![Penn]()

Marvin Penn in Spain. RGASPI, Fond 545, Opis 6, Delo 558

Penn, Marvin. (Palmer; Michael; Pen; Penas); b September 9, 1913, Vilna, Lithuania, To Canada 1926; Jewish; Parents Joseph and Anna Penn, Siblings Aaron, Victor and Rose; Militia 1935-1937, LAMC 3rd Field Ambulance; Fur Dresser and Miner; Domicile Winnipeg; YCL 1930, CP June 1937, Jewish Progrssive Youth Club; Arrived in Spain March 17, 1937; Served with the XV BDE, Lincoln BN; Mackenzie-Papineau BN; First Aid work at Albacete at beginning; later Karl Marx barracks in Barcelona; Served at Jarama, Brunete, Guadalajar, Quntio and Belchite; WIA at Brunete; Returned to Canada 1939; MacPap Veterans Association (Toronto); d. April 3, 2001.

Sources; RGASPI Fond 545, Opis 6, Delo 558, ll. 83-88; Delo 563, ll. 82; Momryk; Petrou; Obituary, Winnipeg Free Press, April 5, 2001, http://passages.winnipegfreepress.com/passage-details/id-60313/name-Marvin_Penn/

Rickards, Joseph. (Richards; Wood; John; Rick; Charles); b. April 5, 1917, Winnipeg; French Canadian; Single; Laborer; Domicile German, Vancouver; Winnipeg (Bonavist); CPC 1935; To Spain March 2, 1937; Served with the XV BDE, Lincoln BN, Co. 1, April 15 to August 18, 1937; Later with 152 and 4th Groups Artillery; Rank Soldado; Served at Villanueva de la Canada, Brunete, Pardillo Levante; Returned to Canada February 11, 1939; After return was placed in a mental institution where he remained until his death.

Sources: RGASPI Fond 545, Opis 6, Delo 565, ll. 56-57; Momryk; Petrou.

Russel, Tomasz. (Russell; Rosol; Thomas); b. circa 1899, Lopuchovo, Poland, To Canada 1925; Polish; Polish Army; Carpenter; Domicile Montreal, Quebec and Toronto, Ontario; CPC 1933; Arrived in Spain January 28, 1937; Served in the XV BDE, Lincoln BN, Co. 1; Returned to Canada on October 18, 1937.

Sources: RGASPI Fond 545, Opis 6, Delo 567, ll. 32 (fiche only); Momryk; Petrou; Polek Hurrah Revolutionaries and Polish Patriots.

k-Ryant, Tommy. (Rubin, Reuben); b. circa 1913, Edmonton, Montreal; US Army National Guard; Domicile USA; YCL; Arrived in Spain February 1, 1937 from New York; Captured and executed March 10-17, 1938, Belchite, during the Retreats.

Sources: Momryk; Petrou.

![Walthers]()

Charles Walthers of Vancouver, British Columbia, who was killed at Belchite, during the Spanish Civil War, 1936-1938. MIKAN 3222108

k-Walthers, Charles Henry. (Sands; Walters; Walther); b. circa 1897; German; WWI German Army 3 years and in the German Revolution rose to Sergeant, Later US Army Corporal; Gunsmith and Miner; Domicile Vancouver, British Columbia; CP of Germany 1917-1922 (Spartucus); CPC 1935, unit organizer; Served with the XV BDE, Lincoln BN; KIA September 6, 1937, Belchite, died of wounds.

Sources: List of Canadian Casualties in Spain MG30 E173 Vol.1 File 13; RGASPI Fond 545, Opis 6, Delo 575, ll. 10; Momryk; Petrou.

Yaworski, Stanley. (Yaworsky; Yawasky; Jaworski); Ukrainian; b. November 7, 1916, Winnipeg; Single; Domicile 583 Dundas Street West, Toronto, Ontario; No Party; Arrived in Spain on April 3, 1937; Trained at Madrigueras; Served with the XV BDE, Dimitrov BN in Madrigueras, Transferred to Lincoln BN on May 13, 1937; and Mackenzie-Papineau BN, Co. 2; November 11, 1937; Observer and machine gunner; WIA June 1, 1937 Jarama hit in both legs when bullets hit the shield of his MG and ricocheted off, In hospital at Castelyo June 3, 1937-July 3, 1937; WIA February 3, 1938 in head while observing through a loophole, in hospital at Segerde (Passionaria 2) and Albacete February 3, – March 31, 1938; Broke left foot during Ebro Offensive, in hospital at Mataro July 28-August 19, 1938; Served at Jarama April 15 – June 15, 1937, Centre, Teruel December 14, 1937-February 3, 1938; and Ebro Offensive July 25-27, 1938; Jailed for 14 days in Castel de Fels for taking 6 days leave without permission, in August 1938, considered the punishment to be unjust; Returned to Canada in 1939.

Sources: RGASPI Fond 545, Opis 6, Delo 576, ll. 10-27; Momryk; Petrou.

Zagar, Mijo. (Zgar, Mike A.; Miho; Mijo; Majk); b. 1904 Delnice Croatia, To Canada 1926, Domiciled alien; Croat; Single; Laborer and Miner; Domicile Montreal; Ville De Sale; CPC 1933 or 1934; Arrived in Spain January 22 (16, 20), 1937, travelled on a Canadian Passport, expired on January 7, 1938; Served with the XV BDE, Lincoln Battalion, Co. 1; and Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion; later with American anti-tank A-A battery (35th Battery); Served at Jarama, Brunete, Teruel; Castellon; and Levante; WIA July 1937, Brunete; Returned to Canada in 1939; Later to Yugoslavia as part of Radnik movement.

Sources: RA Fond 545, Opis 6, Delo 537; Fond 545, Opis 6, Delo 576; Kraljic; Momryk; Petrou.

Share